eBPF 入门开发实践教程一:介绍 eBPF 的基本概念、常见的开发工具

1. eBPF简介:安全和有效地扩展内核

eBPF 是一项革命性的技术,起源于 Linux 内核,可以在操作系统的内核中运行沙盒程序。它被用来安全和有效地扩展内核的功能,而不需要改变内核的源代码或加载内核模块。eBPF 通过允许在操作系统内运行沙盒程序,应用程序开发人员可以在运行时,可编程地向操作系统动态添加额外的功能。然后,操作系统保证安全和执行效率,就像在即时编译(JIT)编译器和验证引擎的帮助下进行本地编译一样。eBPF 程序在内核版本之间是可移植的,并且可以自动更新,从而避免了工作负载中断和节点重启。

今天,eBPF被广泛用于各类场景:在现代数据中心和云原生环境中,可以提供高性能的网络包处理和负载均衡;以非常低的资源开销,做到对多种细粒度指标的可观测性,帮助应用程序开发人员跟踪应用程序,为性能故障排除提供洞察力;保障应用程序和容器运行时的安全执行,等等。可能性是无穷的,而 eBPF 在操作系统内核中所释放的创新才刚刚开始[3]。

eBPF 的未来:内核的 JavaScript 可编程接口

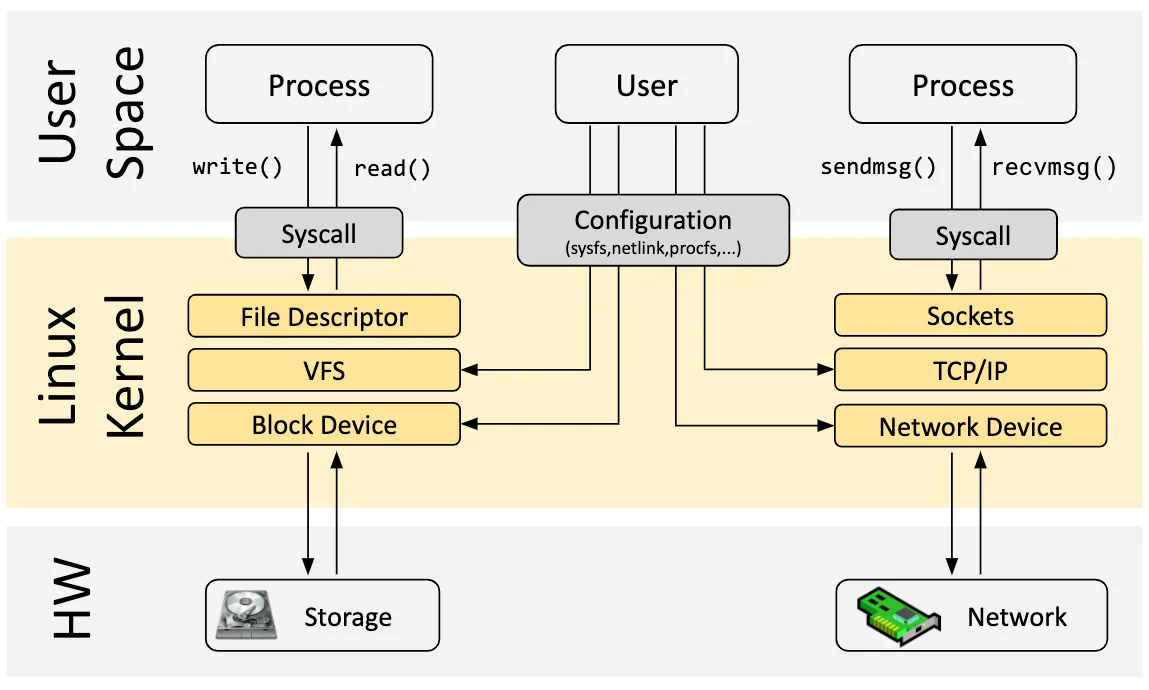

对于浏览器而言,JavaScript 的引入带来的可编程性开启了一场巨大的革命,使浏览器发展成为几乎独立的操作系统。现在让我们回到 eBPF:为了理解 eBPF 对 Linux 内核的可编程性影响,对 Linux 内核的结构以及它如何与应用程序和硬件进行交互有一个高层次的理解是有帮助的[4]。

Linux 内核的主要目的是抽象出硬件或虚拟硬件,并提供一个一致的API(系统调用),允许应用程序运行和共享资源。为了实现这个目的,我们维护了一系列子系统和层,以分配这些责任[5]。每个子系统通常允许某种程度的配置,以考虑到用户的不同需求。如果不能配置所需的行为,就需要改变内核,从历史上看,改变内核的行为,或者让用户编写的程序能够在内核中运行,就有两种选择:

| 本地支持内核模块 | 写一个内核模块 |

|---|---|

| 改变内核源代码,并说服Linux内核社区相信这种改变是必要的。等待几年,让新的内核版本成为一种商品。 | 定期修复它,因为每个内核版本都可能破坏它。由于缺乏安全边界,冒着破坏你的Linux内核的风险 |

实际上,两种方案都不常用,前者成本太高,后者则几乎没有可移植性。

有了 eBPF,就有了一个新的选择,可以重新编程 Linux 内核的行为,而不需要改变内核的源代码或加载内核模块,同时保证在不同内核版本之间一定程度上的行为一致性和兼容性、以及安全性[6]。为了实现这个目的,eBPF 程序也需要有一套对应的 API,允许用户定义的应用程序运行和共享资源 --- 换句话说,某种意义上讲 eBPF 虚拟机也提供了一套类似于系统调用的机制,借助 eBPF 和用户态通信的机制,Wasm 虚拟机和用户态应用也可以获得这套“系统调用”的完整使用权,一方面能可编程地扩展传统的系统调用的能力,另一方面能在网络、文件系统等许多层次实现更高效的可编程 IO 处理。

正如上图所示,当今的 Linux 内核正在向一个新的内核模型演化:用户定义的应用程序可以在内核态和用户态同时执行,用户态通过传统的系统调用访问系统资源,内核态则通过 BPF Helper Calls 和系统的各个部分完成交互。截止 2023 年初,内核中的 eBPF 虚拟机中已经有 220 多个Helper 系统接口,涵盖了非常多的应用场景。

值得注意的是,BPF Helper Call 和系统调用二者并不是竞争关系,它们的编程模型和有性能优势的场景完全不同,也不会完全替代对方。对 Wasm 和 Wasi 相关生态来说,情况也类似,专门设计的 wasi 接口需要经历一个漫长的标准化过程,但可能在特定场景能为用户态应用获取更佳的性能和可移植性保证,而 eBPF 在保证沙箱本质和可移植性的前提下,可以提供一个快速灵活的扩展系统接口的方案。

目前的 eBPF 仍然处于早期阶段,但是借助当前 eBPF 提供的内核接口和用户态交互的能力,经由 Wasm-bpf 的系统接口转换,Wasm 虚拟机中的应用已经几乎有能力获取内核以及用户态任意一个函数调用的数据和返回值(kprobe,uprobe...);以很低的代价收集和理解所有系统调用,并获取所有网络操作的数据包和套接字级别的数据(tracepoint,socket...);在网络包处理解决方案中添加额外的协议分析器,并轻松地编程任何转发逻辑(XDP,TC...),以满足不断变化的需求,而无需离开Linux内核的数据包处理环境。

不仅如此,eBPF 还有能力往用户空间任意进程的任意地址写入数据(bpf_probe_write_user[7]),有限度地修改内核函数的返回值(bpf_override_return[8]),甚至在内核态直接执行某些系统调用[9];所幸的是,eBPF 在加载进内核之前对字节码会进行严格的安全检查,确保没有内存越界等操作,同时,许多可能会扩大攻击面、带来安全风险的功能都是需要在编译内核时明确选择启用才能使用的;在 Wasm 虚拟机将字节码加载进内核之前,也可以明确选择启用或者禁用某些 eBPF 功能,以确保沙箱的安全性。

2. 关于如何学习 eBPF 相关的开发的一些建议

本文不会对 eBPF 的原理做更详细的介绍,不过这里有一个学习规划和参考资料,也许会有一些价值:

eBPF 入门(5-7h)

- Google 或者其他搜索引擎查找:eBPF

- 询问 ChatGPT 之类的东西:eBPF 是什么?

推荐:

- 阅读 ebpf 简介:https://ebpf.io/ (30min)

- 简要了解一下 ebpf 内核相关文档:https://prototype-kernel.readthedocs.io/en/latest/bpf/ (知道有问题去哪里查询,30min)

- 阅读 ebpf 中文入门指南:https://www.modb.pro/db/391570 (1h)

- 有大量的参考资料:https://github.com/zoidbergwill/awesome-ebpf (2-3h)

- 可以选自己感兴趣的 PPT 翻一翻:https://github.com/gojue/ebpf-slide (1-2h)

回答三个问题:

- 了解 eBPF 是什么东西?为啥要有这个玩意,不能用内核模块?

- 它有什么功能?能在 Linux 内核里面完成哪些事情?有哪些 eBPF 程序的类型和 helper(不需要知道全部,但是需要知道去哪里找)?

- 能拿来做什么?比如说在哪些场景中进行运用?网络、安全、可观测性?

了解如何开发 eBPF 程序(10-15h)

了解并尝试一下 eBPF 开发框架:

- BCC 开发各类小工具的例子:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/docs/tutorial_bcc_python_developer.md (跑一遍,3-4h)

- libbpf 的一些例子:https://github.com/libbpf/libbpf-bootstrap (选感兴趣的运行一下,并阅读一下源代码,2h)

- 基于 libbpf 和 eunomia-bpf 的教程:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial (阅读 1-10 的部分,3-4h)

其他开发框架:Go 语言或者 Rust 语言,请自行搜索并且尝试(0-2h)

有任何问题或者想了解的东西,不管是不是和本项目相关,都可以在本项目的 discussions 里面开始讨论。

回答一些问题,并且进行一些尝试(2-5h):

- 如何开发一个最简单的 eBPF 程序?

- 如何用 eBPF 追踪一个内核功能或函数?有很多种方法,举出对应的代码;

- 有哪些方案能通过用户态和内核态通信?如何从用户态向内核态传送信息?如何从内核态向用户态传递信息?举出代码示例;

- 编写一个你自己的 eBPF 程序,实现一个功能;

- eBPF 程序的整个生命周期里面,分别在用户态和内核态做了哪些事情?

3. 如何使用eBPF编程

原始的eBPF程序编写是非常繁琐和困难的。为了改变这一现状,llvm于2015年推出了可以将由高级语言编写的代码编译为eBPF字节码的功能,同时,eBPF 社区将 bpf() 等原始的系统调用进行了初步地封装,给出了libbpf库。这些库会包含将字节码加载到内核中的函数以及一些其他的关键函数。在Linux的源码包的samples/bpf/目录下,有大量Linux提供的基于libbpf的eBPF样例代码。

一个典型的基于 libbpf 的eBPF程序具有*_kern.c和*_user.c两个文件,*_kern.c中书写在内核中的挂载点以及处理函数,*_user.c中书写用户态代码,完成内核态代码注入以及与用户交互的各种任务。 更为详细的教程可以参考该视频然而由于该方法仍然较难理解且入门存在一定的难度,因此现阶段的eBPF程序开发大多基于一些工具,比如:

- BCC

- BPFtrace

- libbpf-bootstrap

- Go eBPF library

以及还有比较新的工具,例如 eunomia-bpf.

编写 eBPF 程序

eBPF 程序由内核态部分和用户态部分构成。内核态部分包含程序的实际逻辑,用户态部分负责加载和管理内核态部分。使用 eunomia-bpf 开发工具,只需编写内核态部分的代码。

内核态部分的代码需要符合 eBPF 的语法和指令集。eBPF 程序主要由若干个函数组成,每个函数都有其特定的作用。可以使用的函数类型包括:

- kprobe:插探函数,在指定的内核函数前或后执行。

- tracepoint:跟踪点函数,在指定的内核跟踪点处执行。

- raw_tracepoint:原始跟踪点函数,在指定的内核原始跟踪点处执行。

- xdp:网络数据处理函数,拦截和处理网络数据包。

- perf_event:性能事件函数,用于处理内核性能事件。

- kretprobe:函数返回插探函数,在指定的内核函数返回时执行。

- tracepoint_return:跟踪点函数返回,在指定的内核跟踪点返回时执行。

- raw_tracepoint_return:原始跟踪点函数返回,在指定的内核原始跟踪

BCC

BCC全称为BPF Compiler Collection,该项目是一个python库, 包含了完整的编写、编译、和加载BPF程序的工具链,以及用于调试和诊断性能问题的工具。

自2015年发布以来,BCC经过上百位贡献者地不断完善后,目前已经包含了大量随时可用的跟踪工具。其官方项目库 提供了一个方便上手的教程,用户可以快速地根据教程完成BCC入门工作。

用户可以在BCC上使用Python、Lua等高级语言进行编程。 相较于使用C语言直接编程,这些高级语言具有极大的便捷性,用户只需要使用C来设计内核中的 BPF程序,其余包括编译、解析、加载等工作在内,均可由BCC完成。

然而使用BCC存在一个缺点便是在于其兼容性并不好。基于BCC的 eBPF程序每次执行时候都需要进行编译,编译则需要用户配置相关的头文件和对应实现。在实际应用中, 相信大家也会有体会,编译依赖问题是一个很棘手的问题。也正是因此,在本项目的开发中我们放弃了BCC, 选择了可以做到一次编译-多次运行的libbpf-bootstrap工具。

eBPF Go library

eBPF Go库提供了一个通用的eBPF库,它解耦了获取 eBPF 字节码的过程和 eBPF 程序的加载和管理,并实现了类似 libbpf 一样的 CO- 功能。eBPF程序通常是通过编写高级语言创建的,然后使用clang/LLVM编译器编译为eBPF字节码。

libbpf

libbpf-bootstrap是一个基于libbpf库的BPF开发脚手架,从其

github 上可以得到其源码。

libbpf-bootstrap综合了BPF社区过去多年的实践,为开发者提了一个现代化的、便捷的工作流,实

现了一次编译,重复使用的目的。

基于libbpf-bootstrap的BPF程序对于源文件有一定的命名规则,

用于生成内核态字节码的bpf文件以.bpf.c结尾,用户态加载字节码的文件以.c结尾,且这两个文件的

前缀必须相同。

基于libbpf-bootstrap的BPF程序在编译时会先将*.bpf.c文件编译为

对应的.o文件,然后根据此文件生成skeleton文件,即*.skel.h,这个文件会包含内核态中定义的一些

数据结构,以及用于装载内核态代码的关键函数。在用户态代码include此文件之后调用对应的装载函数即可将

字节码装载到内核中。同样的,libbpf-bootstrap也有非常完备的入门教程,用户可以在该处

得到详细的入门操作介绍。

eunomia-bpf

开发、构建和分发 eBPF 一直以来都是一个高门槛的工作,使用 BCC、bpftrace 等工具开发效率高、可移植性好,但是分发部署时需要安装 LLVM、Clang等编译环境,每次运行的时候执行本地或远程编译过程,资源消耗较大;使用原生的 CO-RE libbpf时又需要编写不少用户态加载代码来帮助 eBPF 程序正确加载和从内核中获取上报的信息,同时对于 eBPF 程序的分发、管理也没有很好地解决方案。

eunomia-bpf 是一个开源的 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,是为了简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行而设计的,基于 libbpf 的 CO-RE 轻量级开发框架。

使用 eunomia-bpf ,可以:

- 在编写 eBPF 程序或工具时只编写内核态代码,自动获取内核态导出信息,并作为模块动态加载;

- 使用 WASM 进行用户态交互程序的开发,在 WASM 虚拟机内部控制整个 eBPF 程序的加载和执行,以及处理相关数据;

- eunomia-bpf 可以将预编译的 eBPF 程序打包为通用的 JSON 或 WASM 模块,跨架构和内核版本进行分发,无需重新编译即可动态加载运行。

eunomia-bpf 由一个编译工具链和一个运行时库组成, 对比传统的 BCC、原生 libbpf 等框架,大幅简化了 eBPF 程序的开发流程,在大多数时候只需编写内核态代码,即可轻松构建、打包、发布完整的 eBPF 应用,同时内核态 eBPF 代码保证和主流的 libbpf, libbpfgo, libbpf-rs 等开发框架的 100% 兼容性。需要编写用户态代码的时候,也可以借助 Webassembly 实现通过多种语言进行用户态开发。和 bpftrace 等脚本工具相比, eunomia-bpf 保留了类似的便捷性, 同时不仅局限于 trace 方面, 可以用于更多的场景, 如网络、安全等等。

- eunomia-bpf 项目 Github 地址: https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

- gitee 镜像: https://gitee.com/anolis/eunomia

参考资料

- eBPF 介绍:https://ebpf.io/

- BPF Compiler Collection (BCC):https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

- eunomia-bpf:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程二:Hello World,基本框架和开发流程

在本篇博客中,我们将深入探讨eBPF(Extended Berkeley Packet Filter)的基本框架和开发流程。eBPF是一种在Linux内核上运行的强大网络和性能分析工具,它为开发者提供了在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义代码的能力。这使得开发者可以实现高效、安全的内核级别的网络监控、性能分析和故障排查等功能。

本文是eBPF入门开发实践教程的第二篇,我们将重点关注如何编写一个简单的eBPF程序,并通过实际例子演示整个开发流程。在阅读本教程之前,建议您先学习第一篇教程,以便对eBPF的基本概念有个大致的了解。

在开发eBPF程序时,有多种开发框架可供选择,如 BCC(BPF Compiler Collection)libbpf、cilium/ebpf、eunomia-bpf 等。虽然不同工具的特点各异,但它们的基本开发流程大致相同。在接下来的内容中,我们将深入了解这些流程,并以 Hello World 程序为例,带领读者逐步掌握eBPF开发的基本技巧。

本教程将帮助您了解eBPF程序的基本结构、编译和加载过程、用户空间与内核空间的交互方式以及调试与优化技巧。通过学习本教程,您将掌握eBPF开发的基本知识,并为后续进一步学习和实践奠定坚实的基础。

eBPF开发环境准备与基本开发流程

在开始编写eBPF程序之前,我们需要准备一个合适的开发环境,并了解eBPF程序的基本开发流程。本部分将详细介绍这些内容。

安装必要的软件和工具

要开发eBPF程序,您需要安装以下软件和工具:

- Linux 内核:由于eBPF是内核技术,因此您需要具备较新版本的Linux内核(推荐4.8及以上版本),以支持eBPF功能。

- LLVM 和 Clang:这些工具用于编译eBPF程序。安装最新版本的LLVM和Clang可以确保您获得最佳的eBPF支持。

eBPF 程序主要由两部分构成:内核态部分和用户态部分。内核态部分包含 eBPF 程序的实际逻辑,用户态部分负责加载、运行和监控内核态程序。当您选择了合适的开发框架后,如 BCC(BPF Compiler Collection)、libbpf、cilium/ebpf或eunomia-bpf等,您可以开始进行用户态和内核态程序的开发。以 BCC 工具为例,我们将介绍 eBPF 程序的基本开发流程:

当您选择了合适的开发框架后,如BCC(BPF Compiler Collection)、libbpf、cilium/ebpf或eunomia-bpf等,您可以开始进行用户态和内核态程序的开发。以BCC工具为例,我们将介绍eBPF程序的基本开发流程:

- 安装BCC工具:根据您的Linux发行版,按照BCC官方文档的指南安装BCC工具和相关依赖。

- 编写eBPF程序(C语言):使用C语言编写一个简单的eBPF程序,例如Hello World程序。该程序可以在内核空间执行并完成特定任务,如统计网络数据包数量。

- 编写用户态程序(Python或C等):使用Python、C等语言编写用户态程序,用于加载、运行eBPF程序以及与之交互。在这个程序中,您需要使用BCC提供的API来加载和操作内核态的eBPF程序。

- 编译eBPF程序:使用BCC工具,将C语言编写的eBPF程序编译成内核可以执行的字节码。BCC会在运行时动态从源码编译eBPF程序。

- 加载并运行eBPF程序:在用户态程序中,使用BCC提供的API加载编译好的eBPF程序到内核空间,然后运行该程序。

- 与eBPF程序交互:用户态程序通过BCC提供的API与eBPF程序交互,实现数据收集、分析和展示等功能。例如,您可以使用BCC API读取eBPF程序中的map数据,以获取网络数据包统计信息。

- 卸载eBPF程序:当不再需要eBPF程序时,用户态程序应使用BCC API将其从内核空间卸载。

- 调试与优化:使用 bpftool 等工具进行eBPF程序的调试和优化,提高程序性能和稳定性。

通过以上流程,您可以使用BCC工具开发、编译、运行和调试eBPF程序。请注意,其他框架(如libbpf、cilium/ebpf和eunomia-bpf)的开发流程大致相似但略有不同,因此在选择框架时,请参考相应的官方文档和示例。

通过这个过程,你可以开发出一个能够在内核中运行的 eBPF 程序。eunomia-bpf 是一个开源的 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。它基于 libbpf 的 CO-RE 轻量级开发框架,支持通过用户态 WASM 虚拟机控制 eBPF 程序的加载和执行,并将预编译的 eBPF 程序打包为通用的 JSON 或 WASM 模块进行分发。我们会使用 eunomia-bpf 进行演示。

下载安装 eunomia-bpf 开发工具

可以通过以下步骤下载和安装 eunomia-bpf:

下载 ecli 工具,用于运行 eBPF 程序:

$ wget https://aka.pw/bpf-ecli -O ecli && chmod +x ./ecli

$ ./ecli -h

Usage: ecli [--help] [--version] [--json] [--no-cache] url-and-args

下载编译器工具链,用于将 eBPF 内核代码编译为 config 文件或 WASM 模块:

$ wget https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf/releases/latest/download/ecc && chmod +x ./ecc

$ ./ecc -h

eunomia-bpf compiler

Usage: ecc [OPTIONS] <SOURCE_PATH> [EXPORT_EVENT_HEADER]

....

也可以使用 docker 镜像进行编译:

$ docker run -it -v `pwd`/:/src/ yunwei37/ebpm:latest # 使用 docker 进行编译。`pwd` 应该包含 *.bpf.c 文件和 *.h 文件。

export PATH=PATH:~/.eunomia/bin

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into /src/package.json...

Hello World - minimal eBPF program

我们会先从一个简单的 eBPF 程序开始,它会在内核中打印一条消息。我们会使用 eunomia-bpf 的编译器工具链将其编译为 bpf 字节码文件,然后使用 ecli 工具加载并运行该程序。作为示例,我们可以暂时省略用户态程序的部分。

```c

/* SPDX-License-Identifier: (LGPL-2.1 OR BSD-2-Clause) */

#define BPF_NO_GLOBAL_DATA

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

typedef unsigned int u32;

typedef int pid_t;

const pid_t pid_filter = 0;

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

SEC("tp/syscalls/sys_enter_write")

int handle_tp(void *ctx)

{

pid_t pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

if (pid_filter && pid != pid_filter)

return 0;

bpf_printk("BPF triggered from PID %d.\n", pid);

return 0;

}

这段程序通过定义一个 handle_tp 函数并使用 SEC 宏把它附加到 sys_enter_write tracepoint(即在进入 write 系统调用时执行)。该函数通过使用 bpf_get_current_pid_tgid 和 bpf_printk 函数获取调用 write 系统调用的进程 ID,并在内核日志中打印出来。

bpf_trace_printk(): 一种将信息输出到trace_pipe(/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe)简单机制。 在一些简单用例中这样使用没有问题, but它也有一些限制:最多3 参数; 第一个参数必须是%s(即字符串);同时trace_pipe在内核中全局共享,其他并行使用trace_pipe的程序有可能会将 trace_pipe 的输出扰乱。 一个更好的方式是通过 BPF_PERF_OUTPUT(), 稍后将会讲到。void *ctx:ctx本来是具体类型的参数, 但是由于我们这里没有使用这个参数,因此就将其写成void *类型。return 0;:必须这样,返回0 (如果要知道why, 参考 #139 https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/issues/139)。

要编译和运行这段程序,可以使用 ecc 工具和 ecli 命令。首先使用 ecc 编译程序:

$ ecc minimal.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

或使用 docker 镜像进行编译:

docker run -it -v `pwd`/:/src/ yunwei37/ebpm:latest

然后使用 ecli 运行编译后的程序:

$ sudo ecli run ./package.json

Runing eBPF program...

运行这段程序后,可以通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

<...>-3840345 [010] d... 3220701.101143: bpf_trace_printk: write system call from PID 3840345.

<...>-3840345 [010] d... 3220701.101143: bpf_trace_printk: write system call from PID 3840345.

eBPF 程序的基本框架

如上所述, eBPF 程序的基本框架包括:

- 包含头文件:需要包含 <linux/bpf.h> 和 <bpf/bpf_helpers.h> 等头文件。

- 定义许可证:需要定义许可证,通常使用 "Dual BSD/GPL"。

- 定义 BPF 函数:需要定义一个 BPF 函数,例如其名称为 handle_tp,其参数为 void *ctx,返回值为 int。通常用 C 语言编写。

- 使用 BPF 助手函数:在例如 BPF 函数中,可以使用 BPF 助手函数 bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() 和 bpf_printk()。

- 返回值

tracepoints

跟踪点(tracepoints)是内核静态插桩技术,跟踪点在技术上只是放置在内核源代码中的跟踪函数,实际上就是在源码中插入的一些带有控制条件的探测点,这些探测点允许事后再添加处理函数。比如在内核中,最常见的静态跟踪方法就是 printk,即输出日志。又比如:在系统调用、调度程序事件、文件系统操作和磁盘 I/O 的开始和结束时都有跟踪点。 于 2009 年在 Linux 2.6.32 版本中首次提供。跟踪点是一种稳定的 API,数量有限。

GitHub 模板:轻松构建 eBPF 项目和开发环境

面对创建一个 eBPF 项目,您是否对如何开始搭建环境以及选择编程语言感到困惑?别担心,我们为您准备了一系列 GitHub 模板,以便您快速启动一个全新的eBPF项目。只需在GitHub上点击 Use this template 按钮,即可开始使用。

- https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/libbpf-starter-template:基于C语言和 libbpf 框架的eBPF项目模板

- https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/cilium-ebpf-starter-template:基于C语言和cilium/ebpf框架的eBPF项目模板

- https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/libbpf-rs-starter-template:基于Rust语言和libbpf-rs框架的eBPF项目模板

- https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-template:基于C语言和eunomia-bpf框架的eBPF项目模板

这些启动模板包含以下功能:

- 一个 Makefile,让您可以一键构建项目

- 一个 Dockerfile,用于为您的 eBPF 项目自动创建一个容器化环境并发布到 Github Packages

- GitHub Actions,用于自动化构建、测试和发布流程

- eBPF 开发所需的所有依赖项

通过将现有仓库设置为模板,您和其他人可以快速生成具有相同基础结构的新仓库,从而省去了手动创建和配置的繁琐过程。借助 GitHub 模板仓库,开发者可以专注于项目的核心功能和逻辑,而无需为基础设置和结构浪费时间。更多关于模板仓库的信息,请参阅官方文档:https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/creating-and-managing-repositories/creating-a-template-repository

总结

eBPF 程序的开发和使用流程可以概括为如下几个步骤:

- 定义 eBPF 程序的接口和类型:这包括定义 eBPF 程序的接口函数,定义和实现 eBPF 内核映射(maps)和共享内存(perf events),以及定义和使用 eBPF 内核帮助函数(helpers)。

- 编写 eBPF 程序的代码:这包括编写 eBPF 程序的主要逻辑,实现 eBPF 内核映射的读写操作,以及使用 eBPF 内核帮助函数。

- 编译 eBPF 程序:这包括使用 eBPF 编译器(例如 clang)将 eBPF 程序代码编译为 eBPF 字节码,并生成可执行的 eBPF 内核模块。ecc 本质上也是调用 clang 编译器来编译 eBPF 程序。

- 加载 eBPF 程序到内核:这包括将编译好的 eBPF 内核模块加载到 Linux 内核中,并将 eBPF 程序附加到指定的内核事件上。

- 使用 eBPF 程序:这包括监测 eBPF 程序的运行情况,并使用 eBPF 内核映射和共享内存进行数据交换和共享。

- 在实际开发中,还可能需要进行其他的步骤,例如配置编译和加载参数,管理 eBPF 内核模块和内核映射,以及使用其他高级功能等。

需要注意的是,BPF 程序的执行是在内核空间进行的,因此需要使用特殊的工具和技术来编写、编译和调试 BPF 程序。eunomia-bpf 是一个开源的 BPF 编译器和工具包,它可以帮助开发者快速和简单地编写和运行 BPF 程序。

本教程的文档和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程二:在 eBPF 中使用 kprobe 监测捕获 unlink 系统调用

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具。它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第二篇,在 eBPF 中使用 kprobe 捕获 unlink 系统调用。本文会先讲解关于 kprobes 的基本概念和技术背景,然后介绍如何在 eBPF 中使用 kprobe 捕获 unlink 系统调用。

kprobes 技术背景

开发人员在内核或者模块的调试过程中,往往会需要要知道其中的一些函数有无被调用、何时被调用、执行是否正确以及函数的入参和返回值是什么等等。比较简单的做法是在内核代码对应的函数中添加日志打印信息,但这种方式往往需要重新编译内核或模块,重新启动设备之类的,操作较为复杂甚至可能会破坏原有的代码执行过程。

而利用kprobes技术,用户可以定义自己的回调函数,然后在内核或者模块中几乎所有的函数中(有些函数是不可探测的,例如kprobes自身的相关实现函数,后文会有详细说明)动态的插入探测点,当内核执行流程执行到指定的探测函数时,会调用该回调函数,用户即可收集所需的信息了,同时内核最后还会回到原本的正常执行流程。如果用户已经收集足够的信息,不再需要继续探测,则同样可以动态地移除探测点。因此kprobes技术具有对内核执行流程影响小和操作方便的优点。

kprobes技术包括的3种探测手段分别时kprobe、jprobe和kretprobe。首先kprobe是最基本的探测方式,是实现后两种的基础,它可以在任意的位置放置探测点(就连函数内部的某条指令处也可以),它提供了探测点的调用前、调用后和内存访问出错3种回调方式,分别是pre_handler、post_handler和fault_handler,其中pre_handler函数将在被探测指令被执行前回调,post_handler会在被探测指令执行完毕后回调(注意不是被探测函数),fault_handler会在内存访问出错时被调用;jprobe基于kprobe实现,它用于获取被探测函数的入参值;最后kretprobe从名字中就可以看出其用途了,它同样基于kprobe实现,用于获取被探测函数的返回值。

kprobes的技术原理并不仅仅包含存软件的实现方案,它也需要硬件架构提供支持。其中涉及硬件架构相关的是CPU的异常处理和单步调试技术,前者用于让程序的执行流程陷入到用户注册的回调函数中去,而后者则用于单步执行被探测点指令,因此并不是所有的架构均支持,目前kprobes技术已经支持多种架构,包括i386、x86_64、ppc64、ia64、sparc64、arm、ppc和mips(有些架构实现可能并不完全,具体可参考内核的Documentation/kprobes.txt)。

kprobes的特点与使用限制:

- kprobes允许在同一个被被探测位置注册多个kprobe,但是目前jprobe却不可以;同时也不允许以其他的jprobe回调函数和kprobe的post_handler回调函数作为被探测点。

- 一般情况下,可以探测内核中的任何函数,包括中断处理函数。不过在kernel/kprobes.c和arch/*/kernel/kprobes.c程序中用于实现kprobes自身的函数是不允许被探测的,另外还有do_page_fault和notifier_call_chain;

- 如果以一个内联函数为探测点,则kprobes可能无法保证对该函数的所有实例都注册探测点。由于gcc可能会自动将某些函数优化为内联函数,因此可能无法达到用户预期的探测效果;

- 一个探测点的回调函数可能会修改被探测函数运行的上下文,例如通过修改内核的数据结构或者保存与struct pt_regs结构体中的触发探测器之前寄存器信息。因此kprobes可以被用来安装bug修复代码或者注入故障测试代码;

- kprobes会避免在处理探测点函数时再次调用另一个探测点的回调函数,例如在printk()函数上注册了探测点,则在它的回调函数中可能再次调用printk函数,此时将不再触发printk探测点的回调,仅仅时增加了kprobe结构体中nmissed字段的数值;

- 在kprobes的注册和注销过程中不会使用mutex锁和动态的申请内存;

- kprobes回调函数的运行期间是关闭内核抢占的,同时也可能在关闭中断的情况下执行,具体要视CPU架构而定。因此不论在何种情况下,在回调函数中不要调用会放弃CPU的函数(如信号量、mutex锁等);

- kretprobe通过替换返回地址为预定义的trampoline的地址来实现,因此栈回溯和gcc内嵌函数__builtin_return_address()调用将返回trampoline的地址而不是真正的被探测函数的返回地址;

- 如果一个函数的调用次数和返回次数不相等,则在类似这样的函数上注册kretprobe将可能不会达到预期的效果,例如do_exit()函数会存在问题,而do_execve()函数和do_fork()函数不会;

- 如果当在进入和退出一个函数时,CPU运行在非当前任务所有的栈上,那么往该函数上注册kretprobe可能会导致不可预料的后果,因此,kprobes不支持在X86_64的结构下为__switch_to()函数注册kretprobe,将直接返回-EINVAL。

kprobe 示例

完整代码如下:

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

SEC("kprobe/do_unlinkat")

int BPF_KPROBE(do_unlinkat, int dfd, struct filename *name)

{

pid_t pid;

const char *filename;

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

filename = BPF_CORE_READ(name, name);

bpf_printk("KPROBE ENTRY pid = %d, filename = %s\n", pid, filename);

return 0;

}

SEC("kretprobe/do_unlinkat")

int BPF_KRETPROBE(do_unlinkat_exit, long ret)

{

pid_t pid;

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

bpf_printk("KPROBE EXIT: pid = %d, ret = %ld\n", pid, ret);

return 0;

}

这段代码是一个简单的 eBPF 程序,用于监测和捕获在 Linux 内核中执行的 unlink 系统调用。unlink 系统调用的功能是删除一个文件。这个 eBPF 程序通过使用 kprobe(内核探针)在 do_unlinkat 函数的入口和退出处放置钩子,实现对该系统调用的跟踪。

首先,我们导入必要的头文件,如 vmlinux.h,bpf_helpers.h,bpf_tracing.h 和 bpf_core_read.h。接着,我们定义许可证,以允许程序在内核中运行。

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

接下来,我们定义一个名为 BPF_KPROBE(do_unlinkat) 的 kprobe,当进入 do_unlinkat 函数时,它会被触发。该函数接受两个参数:dfd(文件描述符)和 name(文件名结构体指针)。在这个 kprobe 中,我们获取当前进程的 PID(进程标识符),然后读取文件名。最后,我们使用 bpf_printk 函数在内核日志中打印 PID 和文件名。

SEC("kprobe/do_unlinkat")

int BPF_KPROBE(do_unlinkat, int dfd, struct filename *name)

{

pid_t pid;

const char *filename;

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

filename = BPF_CORE_READ(name, name);

bpf_printk("KPROBE ENTRY pid = %d, filename = %s\n", pid, filename);

return 0;

}

接下来,我们定义一个名为 BPF_KRETPROBE(do_unlinkat_exit) 的 kretprobe,当从 do_unlinkat 函数退出时,它会被触发。这个 kretprobe 的目的是捕获函数的返回值(ret)。我们再次获取当前进程的 PID,并使用 bpf_printk 函数在内核日志中打印 PID 和返回值。

SEC("kretprobe/do_unlinkat")

int BPF_KRETPROBE(do_unlinkat_exit, long ret)

{

pid_t pid;

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

bpf_printk("KPROBE EXIT: pid = %d, ret = %ld\n", pid, ret);

return 0;

}

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。

要编译这个程序,请使用 ecc 工具:

$ ecc kprobe-link.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

然后运行:

sudo ecli run package.json

在另外一个窗口中:

touch test1

rm test1

touch test2

rm test2

在 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件中,应该能看到类似下面的 kprobe 演示输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

rm-9346 [005] d..3 4710.951696: bpf_trace_printk: KPROBE ENTRY pid = 9346, filename = test1

rm-9346 [005] d..4 4710.951819: bpf_trace_printk: KPROBE EXIT: ret = 0

rm-9346 [005] d..3 4710.951852: bpf_trace_printk: KPROBE ENTRY pid = 9346, filename = test2

rm-9346 [005] d..4 4710.951895: bpf_trace_printk: KPROBE EXIT: ret = 0

总结

通过本文的示例,我们学习了如何使用 eBPF 的 kprobe 和 kretprobe 捕获 unlink 系统调用。更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第二篇。下一篇文章将介绍如何在 eBPF 中使用 fentry 监测捕获 unlink 系统调用。

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程三:在 eBPF 中使用 fentry 监测捕获 unlink 系统调用

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具。它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第三篇,在 eBPF 中使用 fentry 捕获 unlink 系统调用。

Fentry

fentry(function entry)和fexit(function exit)是eBPF(扩展的伯克利包过滤器)中的两种探针类型,用于在Linux内核函数的入口和退出处进行跟踪。它们允许开发者在内核函数执行的特定阶段收集信息、修改参数或观察返回值。这种跟踪和监控功能在性能分析、故障排查和安全分析等场景中非常有用。

与 kprobes 相比,fentry 和 fexit 程序有更高的性能和可用性。在这个例子中,我们可以直接访问函数的指针参数,就像在普通的 C 代码中一样,而不需要使用各种读取帮助程序。fexit 和 kretprobe 程序最大的区别在于,fexit 程序可以访问函数的输入参数和返回值,而 kretprobe 只能访问返回值。从 5.5 内核开始,fentry 和 fexit 对 eBPF 程序可用。

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

SEC("fentry/do_unlinkat")

int BPF_PROG(do_unlinkat, int dfd, struct filename *name)

{

pid_t pid;

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

bpf_printk("fentry: pid = %d, filename = %s\n", pid, name->name);

return 0;

}

SEC("fexit/do_unlinkat")

int BPF_PROG(do_unlinkat_exit, int dfd, struct filename *name, long ret)

{

pid_t pid;

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

bpf_printk("fexit: pid = %d, filename = %s, ret = %ld\n", pid, name->name, ret);

return 0;

}

这段程序是用C语言编写的eBPF(扩展的伯克利包过滤器)程序,它使用BPF的fentry和fexit探针来跟踪Linux内核函数do_unlinkat。在这个教程中,我们将以这段程序作为示例,让您学会如何在eBPF中使用fentry监测捕获unlink系统调用。

程序包含以下部分:

- 包含头文件:包括vmlinux.h(用于访问内核数据结构)、bpf/bpf_helpers.h(包含eBPF帮助函数)、bpf/bpf_tracing.h(用于eBPF跟踪相关功能)。

- 定义许可证:这里定义了一个名为LICENSE的字符数组,包含许可证信息"Dual BSD/GPL"。

- 定义fentry探针:我们定义了一个名为BPF_PROG(do_unlinkat)的fentry探针,该探针在do_unlinkat函数的入口处被触发。这个探针获取当前进程的PID(进程ID)并将其与文件名一起打印到内核日志。

- 定义fexit探针:我们还定义了一个名为BPF_PROG(do_unlinkat_exit)的fexit探针,该探针在do_unlinkat函数的退出处被触发。与fentry探针类似,这个探针也会获取当前进程的PID并将其与文件名和返回值一起打印到内核日志。

通过这个示例,您可以学习如何在eBPF中使用fentry和fexit探针来监控和捕获内核函数调用,例如在本教程中的unlink系统调用。

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

编译运行上述代码:

$ ecc fentry-link.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

$ sudo ecli run package.json

Runing eBPF program...

在另外一个窗口中:

touch test_file

rm test_file

touch test_file2

rm test_file2

运行这段程序后,可以通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

rm-9290 [004] d..2 4637.798698: bpf_trace_printk: fentry: pid = 9290, filename = test_file

rm-9290 [004] d..2 4637.798843: bpf_trace_printk: fexit: pid = 9290, filename = test_file, ret = 0

rm-9290 [004] d..2 4637.798698: bpf_trace_printk: fentry: pid = 9290, filename = test_file2

rm-9290 [004] d..2 4637.798843: bpf_trace_printk: fexit: pid = 9290, filename = test_file2, ret = 0

总结

这段程序是一个 eBPF 程序,通过使用 fentry 和 fexit 捕获 do_unlinkat 和 do_unlinkat_exit 函数,并通过使用 bpf_get_current_pid_tgid 和 bpf_printk 函数获取调用 do_unlinkat 的进程 ID、文件名和返回值,并在内核日志中打印出来。

编译这个程序可以使用 ecc 工具,运行时可以使用 ecli 命令,并通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件查看 eBPF 程序的输出。更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程四:在 eBPF 中捕获进程打开文件的系统调用集合,使用全局变量过滤进程 pid

eBPF(Extended Berkeley Packet Filter)是一种内核执行环境,它可以让用户在内核中运行一些安全的、高效的程序。它通常用于网络过滤、性能分析、安全监控等场景。eBPF 之所以强大,是因为它能够在内核运行时捕获和修改数据包或者系统调用,从而实现对操作系统行为的监控和调整。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第四篇,主要介绍如何捕获进程打开文件的系统调用集合,并使用全局变量在 eBPF 中过滤进程 pid。

在 Linux 系统中,进程与文件之间的交互是通过系统调用来实现的。系统调用是用户态程序与内核态程序之间的接口,它们允许用户态程序请求内核执行特定操作。在本教程中,我们关注的是 sys_openat 系统调用,它是用于打开文件的。

当进程打开一个文件时,它会向内核发出 sys_openat 系统调用,并传递相关参数(例如文件路径、打开模式等)。内核会处理这个请求,并返回一个文件描述符(file descriptor),这个描述符将在后续的文件操作中用作引用。通过捕获 sys_openat 系统调用,我们可以了解进程在什么时候以及如何打开文件。

在 eBPF 中捕获进程打开文件的系统调用集合

首先,我们需要编写一段 eBPF 程序来捕获进程打开文件的系统调用,具体实现如下:

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

/// @description "Process ID to trace"

const volatile int pid_target = 0;

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_openat")

int tracepoint__syscalls__sys_enter_openat(struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter* ctx)

{

u64 id = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

u32 pid = id;

if (pid_target && pid_target != pid)

return false;

// Use bpf_printk to print the process information

bpf_printk("Process ID: %d enter sys openat\n", pid);

return 0;

}

/// "Trace open family syscalls."

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

这段 eBPF 程序实现了:

- 引入头文件:<vmlinux.h> 包含了内核数据结构的定义,<bpf/bpf_helpers.h> 包含了 eBPF 程序所需的辅助函数。

- 定义全局变量 pid_target,用于过滤指定进程 ID。这里设为 0 表示捕获所有进程的 sys_openat 调用。

- 使用 SEC 宏定义一个 eBPF 程序,关联到 tracepoint "tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_openat"。这个 tracepoint 会在进程发起 sys_openat 系统调用时触发。

- 实现 eBPF 程序 tracepoint__syscalls__sys_enter_openat,它接收一个类型为 struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter 的参数 ctx。这个结构体包含了关于系统调用的信息。

- 使用 bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() 函数获取当前进程的 PID 和 TGID(线程组 ID)。由于我们只关心 PID,所以将其赋值给 u32 类型的变量 pid。

- 检查 pid_target 变量是否与当前进程的 pid 相等。如果 pid_target 不为 0 且与当前进程的 pid 不相等,则返回 false,不对该进程的 sys_openat 调用进行捕获。

- 使用 bpf_printk() 函数打印捕获到的进程 ID 和 sys_openat 调用的相关信息。这些信息将在用户空间通过 BPF 工具查看。

- 将程序许可证设置为 "GPL",这是运行 eBPF 程序的必要条件。

这个 eBPF 程序可以通过 libbpf 或 eunomia-bpf 等工具加载到内核并执行。它将捕获指定进程(或所有进程)的 sys_openat 系统调用,并在用户空间输出相关信息。

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

编译运行上述代码:

$ ecc opensnoop.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

$ sudo ecli run package.json

Runing eBPF program...

运行这段程序后,可以通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

<...>-3840345 [010] d... 3220701.101179: bpf_trace_printk: Process ID: 3840345 enter sys openat

<...>-3840345 [010] d... 3220702.158000: bpf_trace_printk: Process ID: 3840345 enter sys openat

此时,我们已经能够捕获进程打开文件的系统调用了。

使用全局变量在 eBPF 中过滤进程 pid

全局变量在 eBPF 程序中充当一种数据共享机制,它们允许用户态程序与 eBPF 程序之间进行数据交互。这在过滤特定条件或修改 eBPF 程序行为时非常有用。这种设计使得用户态程序能够在运行时动态地控制 eBPF 程序的行为。

在我们的例子中,全局变量 pid_target 用于过滤进程 PID。用户态程序可以设置此变量的值,以便在 eBPF 程序中只捕获与指定 PID 相关的 sys_openat 系统调用。

使用全局变量的原理是,全局变量在 eBPF 程序的数据段(data section)中定义并存储。当 eBPF 程序加载到内核并执行时,这些全局变量会保持在内核中,可以通过 BPF 系统调用进行访问。用户态程序可以使用 BPF 系统调用中的某些特性,如 bpf_obj_get_info_by_fd 和 bpf_obj_get_info,获取 eBPF 对象的信息,包括全局变量的位置和值。

可以通过执行 ecli -h 命令来查看 opensnoop 的帮助信息:

$ ecli package.json -h

Usage: opensnoop_bpf [--help] [--version] [--verbose] [--pid_target VAR]

Trace open family syscalls.

Optional arguments:

-h, --help shows help message and exits

-v, --version prints version information and exits

--verbose prints libbpf debug information

--pid_target Process ID to trace

Built with eunomia-bpf framework.

See https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf for more information.

可以通过 --pid_target 参数来指定要捕获的进程的 pid,例如:

$ sudo ./ecli run package.json --pid_target 618

Runing eBPF program...

运行这段程序后,可以通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

<...>-3840345 [010] d... 3220701.101179: bpf_trace_printk: Process ID: 618 enter sys openat

<...>-3840345 [010] d... 3220702.158000: bpf_trace_printk: Process ID: 618 enter sys openat

总结

本文介绍了如何使用 eBPF 程序来捕获进程打开文件的系统调用。在 eBPF 程序中,我们可以通过定义 tracepoint__syscalls__sys_enter_open 和 tracepoint__syscalls__sys_enter_openat 函数并使用 SEC 宏把它们附加到 sys_enter_open 和 sys_enter_openat 两个 tracepoint 来捕获进程打开文件的系统调用。我们可以使用 bpf_get_current_pid_tgid 函数获取调用 open 或 openat 系统调用的进程 ID,并使用 bpf_printk 函数在内核日志中打印出来。在 eBPF 程序中,我们还可以通过定义一个全局变量 pid_target 来指定要捕获的进程的 pid,从而过滤输出,只输出指定的进程的信息。

通过学习本教程,您应该对如何在 eBPF 中捕获和过滤特定进程的系统调用有了更深入的了解。这种方法在系统监控、性能分析和安全审计等场景中具有广泛的应用。

更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程五:在 eBPF 中使用 uprobe 捕获 bash 的 readline 函数调用

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具,它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第五篇,主要介绍如何使用 uprobe 捕获 bash 的 readline 函数调用。

什么是uprobe

uprobe是一种用户空间探针,uprobe探针允许在用户空间程序中动态插桩,插桩位置包括:函数入口、特定偏移处,以及函数返回处。当我们定义uprobe时,内核会在附加的指令上创建快速断点指令(x86机器上为int3指令),当程序执行到该指令时,内核将触发事件,程序陷入到内核态,并以回调函数的方式调用探针函数,执行完探针函数再返回到用户态继续执行后序的指令。

uprobe基于文件,当一个二进制文件中的一个函数被跟踪时,所有使用到这个文件的进程都会被插桩,包括那些尚未启动的进程,这样就可以在全系统范围内跟踪系统调用。

uprobe适用于在用户态去解析一些内核态探针无法解析的流量,例如http2流量(报文header被编码,内核无法解码),https流量(加密流量,内核无法解密)。

使用 uprobe 捕获 bash 的 readline 函数调用

uprobe 是一种用于捕获用户空间函数调用的 eBPF 的探针,我们可以通过它来捕获用户空间程序调用的系统函数。

例如,我们可以使用 uprobe 来捕获 bash 的 readline 函数调用,从而获取用户在 bash 中输入的命令行。示例代码如下:

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#define TASK_COMM_LEN 16

#define MAX_LINE_SIZE 80

/* Format of u[ret]probe section definition supporting auto-attach:

* u[ret]probe/binary:function[+offset]

*

* binary can be an absolute/relative path or a filename; the latter is resolved to a

* full binary path via bpf_program__attach_uprobe_opts.

*

* Specifying uprobe+ ensures we carry out strict matching; either "uprobe" must be

* specified (and auto-attach is not possible) or the above format is specified for

* auto-attach.

*/

SEC("uretprobe//bin/bash:readline")

int BPF_KRETPROBE(printret, const void *ret)

{

char str[MAX_LINE_SIZE];

char comm[TASK_COMM_LEN];

u32 pid;

if (!ret)

return 0;

bpf_get_current_comm(&comm, sizeof(comm));

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

bpf_probe_read_user_str(str, sizeof(str), ret);

bpf_printk("PID %d (%s) read: %s ", pid, comm, str);

return 0;

};

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

这段代码的作用是在 bash 的 readline 函数返回时执行指定的 BPF_KRETPROBE 函数,即 printret 函数。

在 printret 函数中,我们首先获取了调用 readline 函数的进程的进程名称和进程 ID,然后通过 bpf_probe_read_user_str 函数读取了用户输入的命令行字符串,最后通过 bpf_printk 函数打印出进程 ID、进程名称和输入的命令行字符串。

除此之外,我们还需要通过 SEC 宏来定义 uprobe 探针,并使用 BPF_KRETPROBE 宏来定义探针函数。

在 SEC 宏中,我们需要指定 uprobe 的类型、要捕获的二进制文件的路径和要捕获的函数名称。例如,上面的代码中的 SEC 宏的定义如下:

SEC("uprobe//bin/bash:readline")

这表示我们要捕获的是 /bin/bash 二进制文件中的 readline 函数。

接下来,我们需要使用 BPF_KRETPROBE 宏来定义探针函数,例如:

BPF_KRETPROBE(printret, const void *ret)

这里的 printret 是探针函数的名称,const void *ret 是探针函数的参数,它代表被捕获的函数的返回值。

然后,我们使用了 bpf_get_current_comm 函数获取当前任务的名称,并将其存储在 comm 数组中。

bpf_get_current_comm(&comm, sizeof(comm));

使用 bpf_get_current_pid_tgid 函数获取当前进程的 PID,并将其存储在 pid 变量中。

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

使用 bpf_probe_read_user_str 函数从用户空间读取 readline 函数的返回值,并将其存储在 str 数组中。

bpf_probe_read_user_str(str, sizeof(str), ret);

最后使用 bpf_printk 函数输出 PID、任务名称和用户输入的字符串。

bpf_printk("PID %d (%s) read: %s ", pid, comm, str);

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

编译运行上述代码:

$ ecc bashreadline.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

$ sudo ecli run package.json

Runing eBPF program...

运行这段程序后,可以通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

bash-32969 [000] d..31 64001.375748: bpf_trace_printk: PID 32969 (bash) read: fff

bash-32969 [000] d..31 64002.056951: bpf_trace_printk: PID 32969 (bash) read: fff

可以看到,我们成功的捕获了 bash 的 readline 函数调用,并获取了用户在 bash 中输入的命令行。

总结

在上述代码中,我们使用了 SEC 宏来定义了一个 uprobe 探针,它指定了要捕获的用户空间程序 (bin/bash) 和要捕获的函数 (readline)。此外,我们还使用了 BPF_KRETPROBE 宏来定义了一个用于处理 readline 函数返回值的回调函数 (printret)。该函数可以获取到 readline 函数的返回值,并将其打印到内核日志中。通过这样的方式,我们就可以使用 eBPF 来捕获 bash 的 readline 函数调用,并获取用户在 bash 中输入的命令行。

更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程六:捕获进程发送信号的系统调用集合,使用 hash map 保存状态

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具,它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第六篇,主要介绍如何实现一个 eBPF 工具,捕获进程发送信号的系统调用集合,使用 hash map 保存状态。

sigsnoop

示例代码如下:

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#define MAX_ENTRIES 10240

#define TASK_COMM_LEN 16

struct event {

unsigned int pid;

unsigned int tpid;

int sig;

int ret;

char comm[TASK_COMM_LEN];

};

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, MAX_ENTRIES);

__type(key, __u32);

__type(value, struct event);

} values SEC(".maps");

static int probe_entry(pid_t tpid, int sig)

{

struct event event = {};

__u64 pid_tgid;

__u32 tid;

pid_tgid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

tid = (__u32)pid_tgid;

event.pid = pid_tgid >> 32;

event.tpid = tpid;

event.sig = sig;

bpf_get_current_comm(event.comm, sizeof(event.comm));

bpf_map_update_elem(&values, &tid, &event, BPF_ANY);

return 0;

}

static int probe_exit(void *ctx, int ret)

{

__u64 pid_tgid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

__u32 tid = (__u32)pid_tgid;

struct event *eventp;

eventp = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&values, &tid);

if (!eventp)

return 0;

eventp->ret = ret;

bpf_printk("PID %d (%s) sent signal %d to PID %d, ret = %d",

eventp->pid, eventp->comm, eventp->sig, eventp->tpid, ret);

cleanup:

bpf_map_delete_elem(&values, &tid);

return 0;

}

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_kill")

int kill_entry(struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter *ctx)

{

pid_t tpid = (pid_t)ctx->args[0];

int sig = (int)ctx->args[1];

return probe_entry(tpid, sig);

}

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_exit_kill")

int kill_exit(struct trace_event_raw_sys_exit *ctx)

{

return probe_exit(ctx, ctx->ret);

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

上面的代码定义了一个 eBPF 程序,用于捕获进程发送信号的系统调用,包括 kill、tkill 和 tgkill。它通过使用 tracepoint 来捕获系统调用的进入和退出事件,并在这些事件发生时执行指定的探针函数,例如 probe_entry 和 probe_exit。

在探针函数中,我们使用 bpf_map 存储捕获的事件信息,包括发送信号的进程 ID、接收信号的进程 ID、信号值和系统调用的返回值。在系统调用退出时,我们将获取存储在 bpf_map 中的事件信息,并使用 bpf_printk 打印进程 ID、进程名称、发送的信号和系统调用的返回值。

最后,我们还需要使用 SEC 宏来定义探针,并指定要捕获的系统调用的名称,以及要执行的探针函数。

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

编译运行上述代码:

docker run -it -v `pwd`/:/src/ yunwei37/ebpm:latest

或者

$ ecc sigsnoop.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Generating export types...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

$ sudo ecli run package.json

Runing eBPF program...

运行这段程序后,可以通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出:

$ sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

node-3517 [003] d..31 82575.798191: bpf_trace_printk: PID 3517 (node) sent signal 0 to PID 3427, ret = 0

node-15194 [003] d..31 82575.849227: bpf_trace_printk: PID 15194 (node) sent signal 0 to PID 3427, ret = 0

node-30016 [003] d..31 82576.001361: bpf_trace_printk: PID 30016 (node) sent signal 0 to PID 3427, ret = 0

cpptools-srv-38617 [002] d..31 82576.461085: bpf_trace_printk: PID 38617 (cpptools-srv) sent signal 0 to PID 30496, ret = 0

node-30040 [002] d..31 82576.467720: bpf_trace_printk: PID 30016 (node) sent signal 0 to PID 3427, ret = 0

总结

本文主要介绍如何实现一个 eBPF 工具,捕获进程发送信号的系统调用集合,使用 hash map 保存状态。使用 hash map 需要定义一个结构体:

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, MAX_ENTRIES);

__type(key, __u32);

__type(value, struct event);

} values SEC(".maps");

并使用一些对应的 API 进行访问,例如 bpf_map_lookup_elem、bpf_map_update_elem、bpf_map_delete_elem 等。

更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门实践教程七:捕获进程执行/退出时间,通过 perf event array 向用户态打印输出

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具,它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第七篇,主要介绍如何捕获 Linux 内核中进程执行的事件,并且通过 perf event array 向用户态命令行打印输出,不需要再通过查看 /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe 文件来查看 eBPF 程序的输出。通过 perf event array 向用户态发送信息之后,可以进行复杂的数据处理和分析。

perf buffer

eBPF 提供了两个环形缓冲区,可以用来将信息从 eBPF 程序传输到用户区控制器。第一个是perf环形缓冲区,,它至少从内核v4.15开始就存在了。第二个是后来引入的 BPF 环形缓冲区。本文只考虑perf环形缓冲区。

execsnoop

通过 perf event array 向用户态命令行打印输出,需要编写一个头文件,一个 C 源文件。示例代码如下:

头文件:execsnoop.h

#ifndef __EXECSNOOP_H

#define __EXECSNOOP_H

#define TASK_COMM_LEN 16

struct event {

int pid;

int ppid;

int uid;

int retval;

bool is_exit;

char comm[TASK_COMM_LEN];

};

#endif /* __EXECSNOOP_H */

源文件:execsnoop.bpf.c

// SPDX-License-Identifier: (LGPL-2.1 OR BSD-2-Clause)

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include "execsnoop.h"

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_PERF_EVENT_ARRAY);

__uint(key_size, sizeof(u32));

__uint(value_size, sizeof(u32));

} events SEC(".maps");

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_execve")

int tracepoint__syscalls__sys_enter_execve(struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter* ctx)

{

u64 id;

pid_t pid, tgid;

struct event event={0};

struct task_struct *task;

uid_t uid = (u32)bpf_get_current_uid_gid();

id = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

pid = (pid_t)id;

tgid = id >> 32;

event.pid = tgid;

event.uid = uid;

task = (struct task_struct*)bpf_get_current_task();

event.ppid = BPF_CORE_READ(task, real_parent, tgid);

bpf_get_current_comm(&event.comm, sizeof(event.comm));

bpf_perf_event_output(ctx, &events, BPF_F_CURRENT_CPU, &event, sizeof(event));

return 0;

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

这段代码定义了个 eBPF 程序,用于捕获进程执行 execve 系统调用的入口。

在入口程序中,我们首先获取了当前进程的进程 ID 和用户 ID,然后通过 bpf_get_current_task 函数获取了当前进程的 task_struct 结构体,并通过 bpf_probe_read_str 函数读取了进程名称。最后,我们通过 bpf_perf_event_output 函数将进程执行事件输出到 perf buffer。

使用这段代码,我们就可以捕获 Linux 内核中进程执行的事件, 并分析进程的执行情况。

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

使用容器编译:

docker run -it -v `pwd`/:/src/ yunwei37/ebpm:latest

或者使用 ecc 编译:

ecc execsnoop.bpf.c execsnoop.h

运行

$ sudo ./ecli run package.json

TIME PID PPID UID COMM

21:28:30 40747 3517 1000 node

21:28:30 40748 40747 1000 sh

21:28:30 40749 3517 1000 node

21:28:30 40750 40749 1000 sh

21:28:30 40751 3517 1000 node

21:28:30 40752 40751 1000 sh

21:28:30 40753 40752 1000 cpuUsage.sh

总结

本文介绍了如何捕获 Linux 内核中进程执行的事件,并且通过 perf event array 向用户态命令行打印输出,通过 perf event array 向用户态发送信息之后,可以进行复杂的数据处理和分析。在 libbpf 对应的内核态代码中,定义这样一个结构体和对应的头文件:

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_PERF_EVENT_ARRAY);

__uint(key_size, sizeof(u32));

__uint(value_size, sizeof(u32));

} events SEC(".maps");

就可以往用户态直接发送信息。

更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程八:在 eBPF 中使用 exitsnoop 监控进程退出事件,使用 ring buffer 向用户态打印输出

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具。它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第八篇,在 eBPF 中使用 exitsnoop 监控进程退出事件。

ring buffer

现在有一个新的 BPF 数据结构可用。BPF 环形缓冲区(ring buffer)。它解决了 BPF perf buffer(当今从内核向用户空间发送数据的事实上的标准)的内存效率和事件重排问题,同时达到或超过了它的性能。它既提供了与 perf buffer 兼容以方便迁移,又有新的保留/提交API,具有更好的可用性。另外,合成和真实世界的基准测试表明,在几乎所有的情况下,所以考虑将其作为从BPF程序向用户空间发送数据的默认选择。

BPF ringbuf vs BPF perfbuf

今天,只要BPF程序需要将收集到的数据发送到用户空间进行后处理和记录,它通常会使用BPF perf buffer(perfbuf)来实现。Perfbuf 是每个CPU循环缓冲区的集合,它允许在内核和用户空间之间有效地交换数据。它在实践中效果很好,但由于其按CPU设计,它有两个主要的缺点,在实践中被证明是不方便的:内存的低效使用和事件的重新排序。

为了解决这些问题,从Linux 5.8开始,BPF提供了一个新的BPF数据结构(BPF map)。BPF环形缓冲区(ringbuf)。它是一个多生产者、单消费者(MPSC)队列,可以同时在多个CPU上安全共享。

BPF ringbuf 支持来自 BPF perfbuf 的熟悉的功能:

- 变长的数据记录。

- 能够通过内存映射区域有效地从用户空间读取数据,而不需要额外的内存拷贝和/或进入内核的系统调用。

- 既支持epoll通知,又能以绝对最小的延迟进行忙环操作。

同时,BPF ringbuf解决了BPF perfbuf的以下问题:

- 内存开销。

- 数据排序。

- 浪费的工作和额外的数据复制。

exitsnoop

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第八篇,在 eBPF 中使用 exitsnoop 监控进程退出事件,并使用 ring buffer 向用户态打印输出。

使用 ring buffer 向用户态打印输出的步骤和 perf buffer 类似,首先需要定义一个头文件:

头文件:exitsnoop.h

#ifndef __BOOTSTRAP_H

#define __BOOTSTRAP_H

#define TASK_COMM_LEN 16

#define MAX_FILENAME_LEN 127

struct event {

int pid;

int ppid;

unsigned exit_code;

unsigned long long duration_ns;

char comm[TASK_COMM_LEN];

};

#endif /* __BOOTSTRAP_H */

源文件:exitsnoop.bpf.c

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include "exitsnoop.h"

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF);

__uint(max_entries, 256 * 1024);

} rb SEC(".maps");

SEC("tp/sched/sched_process_exit")

int handle_exit(struct trace_event_raw_sched_process_template* ctx)

{

struct task_struct *task;

struct event *e;

pid_t pid, tid;

u64 id, ts, *start_ts, duration_ns = 0;

/* get PID and TID of exiting thread/process */

id = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

pid = id >> 32;

tid = (u32)id;

/* ignore thread exits */

if (pid != tid)

return 0;

/* reserve sample from BPF ringbuf */

e = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&rb, sizeof(*e), 0);

if (!e)

return 0;

/* fill out the sample with data */

task = (struct task_struct *)bpf_get_current_task();

e->duration_ns = duration_ns;

e->pid = pid;

e->ppid = BPF_CORE_READ(task, real_parent, tgid);

e->exit_code = (BPF_CORE_READ(task, exit_code) >> 8) & 0xff;

bpf_get_current_comm(&e->comm, sizeof(e->comm));

/* send data to user-space for post-processing */

bpf_ringbuf_submit(e, 0);

return 0;

}

这段代码是一个 BPF 程序,用于监控 Linux 系统中的进程退出事件。

该程序通过注册一个 tracepoint,来监控进程退出事件。Tracepoint 是一种内核特性,允许内核模块获取特定事件的通知。在本程序中,注册的 tracepoint 是“tp/sched/sched_process_exit”,表示该程序监控的是进程退出事件。

当系统中发生进程退出事件时,BPF 程序会捕获该事件,并调用“handle_exit”函数来处理它。该函数首先检查当前退出事件是否是进程退出事件(而不是线程退出事件),然后在 BPF 环形缓冲区(“rb”)中保留一个事件结构体,并填充该结构体中的其他信息,例如进程 ID、进程名称、退出代码和退出信号等信息。最后,该函数还会调用 BPF 的“perf_event_output”函数,将捕获的事件发送给用户空间程序。

总而言之,这段代码是一个 BPF 程序,用于监控 Linux 系统中的进程退出事件.

Compile and Run

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

Compile:

docker run -it -v `pwd`/:/src/ yunwei37/ebpm:latest

Or

$ ecc exitsnoop.bpf.c exitsnoop.h

Compiling bpf object...

Generating export types...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

Run:

$ sudo ./ecli run package.json

TIME PID PPID EXIT_CODE DURATION_NS COMM

21:40:09 42050 42049 0 0 which

21:40:09 42049 3517 0 0 sh

21:40:09 42052 42051 0 0 ps

21:40:09 42051 3517 0 0 sh

21:40:09 42055 42054 0 0 sed

21:40:09 42056 42054 0 0 cat

21:40:09 42057 42054 0 0 cat

21:40:09 42058 42054 0 0 cat

21:40:09 42059 42054 0 0 cat

总结

本文介绍了如何使用 eunomia-bpf 开发一个简单的 BPF 程序,该程序可以监控 Linux 系统中的进程退出事件, 并将捕获的事件通过 ring buffer 发送给用户空间程序。在本文中,我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行了这个例子。如果你想了解更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程九:一个 Linux 内核 BPF 程序,通过柱状图来总结调度程序运行队列延迟,显示任务等待运行在 CPU 上的时间长度

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具。它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

runqlat是什么?

bcc-tools 是一组用于在 Linux 系统上使用 BPF 程序的工具。runqlat 是 bcc-tools 中的一个工具,用于分析 Linux 系统的调度性能。具体来说,runqlat 用于测量一个任务在被调度到 CPU 上运行之前在运行队列中等待的时间。这些信息对于识别性能瓶颈和提高 Linux 内核调度算法的整体效率非常有用。

runqlat 原理

runqlat 使用内核跟踪点和函数探针的结合来测量进程在运行队列中的时间。当进程被排队时,trace_enqueue 函数会在一个映射中记录时间戳。当进程被调度到 CPU 上运行时,handle_switch 函数会检索时间戳,并计算当前时间与排队时间之间的时间差。这个差值(或 delta)然后用于更新进程的直方图,该直方图记录运行队列延迟的分布。该直方图可用于分析 Linux 内核的调度性能。

runqlat 代码实现

首先我们需要编写一个源代码文件 runqlat.bpf.c:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-2.0

// Copyright (c) 2020 Wenbo Zhang

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include "runqlat.h"

#include "bits.bpf.h"

#include "maps.bpf.h"

#include "core_fixes.bpf.h"

#define MAX_ENTRIES 10240

#define TASK_RUNNING 0

const volatile bool filter_cg = false;

const volatile bool targ_per_process = false;

const volatile bool targ_per_thread = false;

const volatile bool targ_per_pidns = false;

const volatile bool targ_ms = false;

const volatile pid_t targ_tgid = 0;

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_CGROUP_ARRAY);

__type(key, u32);

__type(value, u32);

__uint(max_entries, 1);

} cgroup_map SEC(".maps");

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, MAX_ENTRIES);

__type(key, u32);

__type(value, u64);

} start SEC(".maps");

static struct hist zero;

/// @sample {"interval": 1000, "type" : "log2_hist"}

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, MAX_ENTRIES);

__type(key, u32);

__type(value, struct hist);

} hists SEC(".maps");

static int trace_enqueue(u32 tgid, u32 pid)

{

u64 ts;

if (!pid)

return 0;

if (targ_tgid && targ_tgid != tgid)

return 0;

ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

bpf_map_update_elem(&start, &pid, &ts, BPF_ANY);

return 0;

}

static unsigned int pid_namespace(struct task_struct *task)

{

struct pid *pid;

unsigned int level;

struct upid upid;

unsigned int inum;

/* get the pid namespace by following task_active_pid_ns(),

* pid->numbers[pid->level].ns

*/

pid = BPF_CORE_READ(task, thread_pid);

level = BPF_CORE_READ(pid, level);

bpf_core_read(&upid, sizeof(upid), &pid->numbers[level]);

inum = BPF_CORE_READ(upid.ns, ns.inum);

return inum;

}

static int handle_switch(bool preempt, struct task_struct *prev, struct task_struct *next)

{

struct hist *histp;

u64 *tsp, slot;

u32 pid, hkey;

s64 delta;

if (filter_cg && !bpf_current_task_under_cgroup(&cgroup_map, 0))

return 0;

if (get_task_state(prev) == TASK_RUNNING)

trace_enqueue(BPF_CORE_READ(prev, tgid), BPF_CORE_READ(prev, pid));

pid = BPF_CORE_READ(next, pid);

tsp = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&start, &pid);

if (!tsp)

return 0;

delta = bpf_ktime_get_ns() - *tsp;

if (delta < 0)

goto cleanup;

if (targ_per_process)

hkey = BPF_CORE_READ(next, tgid);

else if (targ_per_thread)

hkey = pid;

else if (targ_per_pidns)

hkey = pid_namespace(next);

else

hkey = -1;

histp = bpf_map_lookup_or_try_init(&hists, &hkey, &zero);

if (!histp)

goto cleanup;

if (!histp->comm[0])

bpf_probe_read_kernel_str(&histp->comm, sizeof(histp->comm),

next->comm);

if (targ_ms)

delta /= 1000000U;

else

delta /= 1000U;

slot = log2l(delta);

if (slot >= MAX_SLOTS)

slot = MAX_SLOTS - 1;

__sync_fetch_and_add(&histp->slots[slot], 1);

cleanup:

bpf_map_delete_elem(&start, &pid);

return 0;

}

SEC("raw_tp/sched_wakeup")

int BPF_PROG(handle_sched_wakeup, struct task_struct *p)

{

if (filter_cg && !bpf_current_task_under_cgroup(&cgroup_map, 0))

return 0;

return trace_enqueue(BPF_CORE_READ(p, tgid), BPF_CORE_READ(p, pid));

}

SEC("raw_tp/sched_wakeup_new")

int BPF_PROG(handle_sched_wakeup_new, struct task_struct *p)

{

if (filter_cg && !bpf_current_task_under_cgroup(&cgroup_map, 0))

return 0;

return trace_enqueue(BPF_CORE_READ(p, tgid), BPF_CORE_READ(p, pid));

}

SEC("raw_tp/sched_switch")

int BPF_PROG(handle_sched_switch, bool preempt, struct task_struct *prev, struct task_struct *next)

{

return handle_switch(preempt, prev, next);

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

然后我们需要定义一个头文件runqlat.h,用来给用户态处理从内核态上报的事件:

/* SPDX-License-Identifier: (LGPL-2.1 OR BSD-2-Clause) */

#ifndef __RUNQLAT_H

#define __RUNQLAT_H

#define TASK_COMM_LEN 16

#define MAX_SLOTS 26

struct hist {

__u32 slots[MAX_SLOTS];

char comm[TASK_COMM_LEN];

};

#endif /* __RUNQLAT_H */

这是一个 Linux 内核 BPF 程序,旨在收集和报告运行队列的延迟。BPF 是 Linux 内核中一项技术,它允许将程序附加到内核中的特定点并进行安全高效的执行。这些程序可用于收集有关内核行为的信息,并实现自定义行为。这个 BPF 程序使用 BPF maps 来收集有关任务何时从内核的运行队列中排队和取消排队的信息,并记录任务在被安排执行之前在运行队列上等待的时间。然后,它使用这些信息生成直方图,显示不同组任务的运行队列延迟分布。这些直方图可用于识别和诊断内核调度行为中的性能问题。

编译运行

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

Compile:

docker run -it -v `pwd`/:/src/ yunwei37/ebpm:latest

或者

$ ecc runqlat.bpf.c runqlat.h

Compiling bpf object...

Generating export types...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

Run:

$ sudo ecli run examples/bpftools/runqlat/package.json -h

Usage: runqlat_bpf [--help] [--version] [--verbose] [--filter_cg] [--targ_per_process] [--targ_per_thread] [--targ_per_pidns] [--targ_ms] [--targ_tgid VAR]

A simple eBPF program

Optional arguments:

-h, --help shows help message and exits

-v, --version prints version information and exits

--verbose prints libbpf debug information

--filter_cg set value of bool variable filter_cg

--targ_per_process set value of bool variable targ_per_process

--targ_per_thread set value of bool variable targ_per_thread

--targ_per_pidns set value of bool variable targ_per_pidns

--targ_ms set value of bool variable targ_ms

--targ_tgid set value of pid_t variable targ_tgid

Built with eunomia-bpf framework.

See https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf for more information.

$ sudo ecli run examples/bpftools/runqlat/package.json

key = 4294967295

comm = rcu_preempt

(unit) : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 9 |**** |

2 -> 3 : 6 |** |

4 -> 7 : 12 |***** |

8 -> 15 : 28 |************* |

16 -> 31 : 40 |******************* |

32 -> 63 : 83 |****************************************|

64 -> 127 : 57 |*************************** |

128 -> 255 : 19 |********* |

256 -> 511 : 11 |***** |

512 -> 1023 : 2 | |

1024 -> 2047 : 2 | |

2048 -> 4095 : 0 | |

4096 -> 8191 : 0 | |

8192 -> 16383 : 0 | |

16384 -> 32767 : 1 | |

$ sudo ecli run examples/bpftools/runqlat/package.json --targ_per_process

key = 3189

comm = cpptools

(unit) : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 1 |*** |

16 -> 31 : 2 |******* |

32 -> 63 : 11 |****************************************|

64 -> 127 : 8 |***************************** |

128 -> 255 : 3 |********** |

总结

runqlat 是一个 Linux 内核 BPF 程序,通过柱状图来总结调度程序运行队列延迟,显示任务等待运行在 CPU 上的时间长度。编译这个程序可以使用 ecc 工具,运行时可以使用 ecli 命令。

runqlat 是一种用于监控Linux内核中进程调度延迟的工具。它可以帮助您了解进程在内核中等待执行的时间,并根据这些信息优化进程调度,提高系统的性能。可以在 libbpf-tools 中找到最初的源代码:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/libbpf-tools/runqlat.bpf.c

更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程十:在 eBPF 中使用 hardirqs 或 softirqs 捕获中断事件

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具。它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

本文是 eBPF 入门开发实践教程的第十篇,在 eBPF 中。

hardirqs是什么?

hardirqs 是 bcc-tools 工具包的一部分,该工具包是一组用于在 Linux 系统上执行系统跟踪和分析的实用程序。 hardirqs 是一种用于跟踪和分析 Linux 内核中的中断处理程序的工具。它使用 BPF(Berkeley Packet Filter)程序来收集有关中断处理程序的数据, 并可用于识别内核中的性能问题和其他与中断处理相关的问题。

实现原理

在 Linux 内核中,每个中断处理程序都有一个唯一的名称,称为中断向量。hardirqs 通过检查每个中断处理程序的中断向量,来监控内核中的中断处理程序。当内核接收到一个中断时,它会查找与该中断相关的中断处理程序,并执行该程序。hardirqs 通过检查内核中执行的中断处理程序,来监控内核中的中断处理程序。另外,hardirqs 还可以通过注入 BPF 程序到内核中,来捕获内核中的中断处理程序。这样,hardirqs 就可以监控内核中执行的中断处理程序,并收集有关它们的信息。

代码实现

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-2.0

// Copyright (c) 2020 Wenbo Zhang

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include "hardirqs.h"

#include "bits.bpf.h"

#include "maps.bpf.h"

#define MAX_ENTRIES 256

const volatile bool filter_cg = false;

const volatile bool targ_dist = false;

const volatile bool targ_ns = false;

const volatile bool do_count = false;

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_CGROUP_ARRAY);

__type(key, u32);

__type(value, u32);

__uint(max_entries, 1);

} cgroup_map SEC(".maps");

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_PERCPU_ARRAY);

__uint(max_entries, 1);

__type(key, u32);

__type(value, u64);

} start SEC(".maps");

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, MAX_ENTRIES);

__type(key, struct irq_key);

__type(value, struct info);

} infos SEC(".maps");

static struct info zero;

static int handle_entry(int irq, struct irqaction *action)

{

if (filter_cg && !bpf_current_task_under_cgroup(&cgroup_map, 0))

return 0;

if (do_count) {

struct irq_key key = {};

struct info *info;

bpf_probe_read_kernel_str(&key.name, sizeof(key.name), BPF_CORE_READ(action, name));

info = bpf_map_lookup_or_try_init(&infos, &key, &zero);

if (!info)

return 0;

info->count += 1;

return 0;

} else {

u64 ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

u32 key = 0;

if (filter_cg && !bpf_current_task_under_cgroup(&cgroup_map, 0))

return 0;

bpf_map_update_elem(&start, &key, &ts, BPF_ANY);

return 0;

}

}

static int handle_exit(int irq, struct irqaction *action)

{

struct irq_key ikey = {};

struct info *info;

u32 key = 0;

u64 delta;

u64 *tsp;

if (filter_cg && !bpf_current_task_under_cgroup(&cgroup_map, 0))

return 0;

tsp = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&start, &key);

if (!tsp)

return 0;

delta = bpf_ktime_get_ns() - *tsp;

if (!targ_ns)

delta /= 1000U;

bpf_probe_read_kernel_str(&ikey.name, sizeof(ikey.name), BPF_CORE_READ(action, name));

info = bpf_map_lookup_or_try_init(&infos, &ikey, &zero);

if (!info)

return 0;

if (!targ_dist) {

info->count += delta;

} else {

u64 slot;

slot = log2(delta);

if (slot >= MAX_SLOTS)

slot = MAX_SLOTS - 1;

info->slots[slot]++;

}

return 0;

}

SEC("tp_btf/irq_handler_entry")

int BPF_PROG(irq_handler_entry_btf, int irq, struct irqaction *action)

{

return handle_entry(irq, action);

}

SEC("tp_btf/irq_handler_exit")

int BPF_PROG(irq_handler_exit_btf, int irq, struct irqaction *action)

{

return handle_exit(irq, action);

}

SEC("raw_tp/irq_handler_entry")

int BPF_PROG(irq_handler_entry, int irq, struct irqaction *action)

{

return handle_entry(irq, action);

}

SEC("raw_tp/irq_handler_exit")

int BPF_PROG(irq_handler_exit, int irq, struct irqaction *action)

{

return handle_exit(irq, action);

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

这是一个 BPF(Berkeley Packet Filter)程序。BPF 程序是小型程序,可以直接在 Linux 内核中运行,用于过滤和操纵网络流量。这个特定的程序似乎旨在收集内核中中断处理程序的统计信息。它定义了一些 maps (可以在 BPF 程序和内核的其他部分之间共享的数据结构)和两个函数:handle_entry 和 handle_exit。当内核进入和退出中断处理程序时,分别执行这些函数。handle_entry 函数用于跟踪中断处理程序被执行的次数,而 handle_exit 则用于测量中断处理程序中花费的时间。

运行代码

eunomia-bpf 是一个结合 Wasm 的开源 eBPF 动态加载运行时和开发工具链,它的目的是简化 eBPF 程序的开发、构建、分发、运行。可以参考 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf 下载和安装 ecc 编译工具链和 ecli 运行时。我们使用 eunomia-bpf 编译运行这个例子。

要编译这个程序,请使用 ecc 工具:

$ ecc hardirqs.bpf.c

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

然后运行:

sudo ecli run ./package.json

总结

更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

完整的教程和源代码已经全部开源,可以在 https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/bpf-developer-tutorial 中查看。

eBPF 入门开发实践教程十一:在 eBPF 中使用 bootstrap 开发用户态程序并跟踪 exec() 和 exit() 系统调用

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) 是 Linux 内核上的一个强大的网络和性能分析工具。它允许开发者在内核运行时动态加载、更新和运行用户定义的代码。

什么是bootstrap?

Bootstrap是一个工具,它使用BPF(Berkeley Packet Filter)程序跟踪执行exec()系统调用(使用SEC(“tp/sched/sched_process_exec”)handle_exit BPF程序),这大致对应于新进程的生成(忽略fork()部分)。此外,它还跟踪exit()(使用SEC(“tp/sched/sched_process_exit”)handle_exit BPF程序)以了解每个进程何时退出。这两个BPF程序共同工作,允许捕获有关任何新进程的有趣信息,例如二进制文件的文件名,以及测量进程的生命周期并在进程死亡时收集有趣的统计信息,例如退出代码或消耗的资源量等。我认为这是深入了解内核内部并观察事物如何真正运作的良好起点。

Bootstrap还使用argp API(libc的一部分)进行命令行参数解析。

Bootstrap

TODO: 添加关于用户态的应用部分,以及关于 libbpf-boostrap 的完整介绍。也许可以参考类似:http://cn-sec.com/archives/1267522.html 的文档。

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-2.0 OR BSD-3-Clause

/* Copyright (c) 2020 Facebook */

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include "bootstrap.h"

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, 8192);

__type(key, pid_t);

__type(value, u64);

} exec_start SEC(".maps");

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF);

__uint(max_entries, 256 * 1024);

} rb SEC(".maps");

const volatile unsigned long long min_duration_ns = 0;

SEC("tp/sched/sched_process_exec")

int handle_exec(struct trace_event_raw_sched_process_exec *ctx)

{

struct task_struct *task;

unsigned fname_off;

struct event *e;

pid_t pid;

u64 ts;

/* remember time exec() was executed for this PID */

pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

bpf_map_update_elem(&exec_start, &pid, &ts, BPF_ANY);

/* don't emit exec events when minimum duration is specified */

if (min_duration_ns)

return 0;

/* reserve sample from BPF ringbuf */

e = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&rb, sizeof(*e), 0);

if (!e)

return 0;

/* fill out the sample with data */

task = (struct task_struct *)bpf_get_current_task();

e->exit_event = false;

e->pid = pid;

e->ppid = BPF_CORE_READ(task, real_parent, tgid);

bpf_get_current_comm(&e->comm, sizeof(e->comm));

fname_off = ctx->__data_loc_filename & 0xFFFF;

bpf_probe_read_str(&e->filename, sizeof(e->filename), (void *)ctx + fname_off);

/* successfully submit it to user-space for post-processing */

bpf_ringbuf_submit(e, 0);

return 0;

}

SEC("tp/sched/sched_process_exit")

int handle_exit(struct trace_event_raw_sched_process_template* ctx)

{

struct task_struct *task;

struct event *e;

pid_t pid, tid;

u64 id, ts, *start_ts, duration_ns = 0;

/* get PID and TID of exiting thread/process */

id = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

pid = id >> 32;

tid = (u32)id;

/* ignore thread exits */

if (pid != tid)

return 0;

/* if we recorded start of the process, calculate lifetime duration */

start_ts = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&exec_start, &pid);

if (start_ts)

duration_ns = bpf_ktime_get_ns() - *start_ts;

else if (min_duration_ns)

return 0;

bpf_map_delete_elem(&exec_start, &pid);

/* if process didn't live long enough, return early */

if (min_duration_ns && duration_ns < min_duration_ns)

return 0;

/* reserve sample from BPF ringbuf */

e = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&rb, sizeof(*e), 0);

if (!e)

return 0;

/* fill out the sample with data */

task = (struct task_struct *)bpf_get_current_task();

e->exit_event = true;

e->duration_ns = duration_ns;

e->pid = pid;

e->ppid = BPF_CORE_READ(task, real_parent, tgid);

e->exit_code = (BPF_CORE_READ(task, exit_code) >> 8) & 0xff;

bpf_get_current_comm(&e->comm, sizeof(e->comm));

/* send data to user-space for post-processing */

bpf_ringbuf_submit(e, 0);

return 0;

}

这是一段使用BPF(Berkeley Packet Filter)的C程序,用于跟踪进程启动和退出事件,并显示有关它们的信息。BPF是一种强大的机制,允许您将称为BPF程序的小程序附加到Linux内核的各个部分。这些程序可用于过滤,监视或修改内核的行为。

程序首先定义一些常量,并包含一些头文件。然后定义了一个名为env的struct,用于存储一些程序选项,例如详细模式和进程报告的最小持续时间。

然后,程序定义了一个名为parse_arg的函数,用于解析传递给程序的命令行参数。它接受三个参数:一个表示正在解析的选项的整数key,一个表示选项参数的字符指针arg和一个表示当前解析状态的struct argp_state指针state。该函数处理选项并在env struct中设置相应的值。

然后,程序定义了一个名为sig_handler的函数,当被调用时会将全局标志exiting设置为true。这用于在接收到信号时允许程序干净地退出。

接下来,我们将继续描述这段代码中的其他部分。

程序定义了一个名为exec_start的BPF map,它的类型为BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH,最大条目数为8192,键类型为pid_t,值类型为u64。

另外,程序还定义了一个名为rb的BPF map,它的类型为BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF,最大条目数为256 * 1024。

程序还定义了一个名为min_duration_ns的常量,其值为0。

程序定义了一个名为handle_exec的SEC(static evaluator of code)函数,它被附加到跟踪进程执行的BPF程序上。该函数记录为该PID执行exec()的时间,并在指定了最小持续时间时不发出exec事件。如果未指定最小持续时间,则会从BPF ringbuf保留样本并使用数据填充样本,然后将其提交给用户空间进行后处理。

程序还定义了一个名为handle_exit的SEC函数,它被附加到跟踪进程退出的BPF程序上。该函数会在确定PID和TID后计算进程的生命周期,然后根据min_duration_ns的值决定是否发出退出事件。如果进程的生命周期足够长,则会从BPF ringbuf保留样本并使用数据填充样本,然后将其提交给用户空间进行后处理。

最后,主函数调用bpf_ringbuf_poll来轮询BPF ringbuf,并在接收到新的事件时处理该事件。这个函数会持续运行,直到全局标志exiting被设置为true,此时它会清理资源并退出。

Install Dependencies

You will need clang, libelf and zlib to build the examples, package names may vary across distros.

On Ubuntu/Debian, you need:

$ apt install clang libelf1 libelf-dev zlib1g-dev

On CentOS/Fedora, you need:

$ dnf install clang elfutils-libelf elfutils-libelf-devel zlib-devel

编译运行

编译运行上述代码:

$ ecc bootstrap.bpf.c bootstrap.h

Compiling bpf object...

Packing ebpf object and config into package.json...

$ sudo ecli run package.json

Runing eBPF program...

总结

这是一个使用BPF的C程序,用于跟踪进程的启动和退出事件,并显示有关这些事件的信息。它通过使用argp API来解析命令行参数,并使用BPF maps 存储进程的信息,包括进程的PID和执行文件的文件名。程序还使用了SEC函数来附加BPF程序,以监视进程的执行和退出事件。最后,程序在终端中打印出启动和退出的进程信息。

编译这个程序可以使用 ecc 工具,运行时可以使用 ecli 命令。更多的例子和详细的开发指南,请参考 eunomia-bpf 的官方文档:https://github.com/eunomia-bpf/eunomia-bpf

eBPF入门实践教程:使用 libbpf-bootstrap 开发程序统计 TCP 连接延时

背景

在互联网后端日常开发接口的时候中,不管你使用的是C、Java、PHP还是Golang,都避免不了需要调用mysql、redis等组件来获取数据,可能还需要执行一些rpc远程调用,或者再调用一些其它restful api。 在这些调用的底层,基本都是在使用TCP协议进行传输。这是因为在传输层协议中,TCP协议具备可靠的连接,错误重传,拥塞控制等优点,所以目前应用比UDP更广泛一些。但相对而言,tcp 连接也有一些缺点,例如建立连接的延时较长等。因此也会出现像 QUIC ,即 快速UDP网络连接 ( Quick UDP Internet Connections )这样的替代方案。

tcp 连接延时分析对于网络性能分析优化或者故障排查都能起到不少作用。

tcpconnlat 的实现原理

tcpconnlat 这个工具跟踪执行活动TCP连接的内核函数 (例如,通过connect()系统调用),并显示本地测量的连接的延迟(时间),即从发送 SYN 到响应包的时间。

tcp 连接原理

tcp 连接的整个过程如图所示:

在这个连接过程中,我们来简单分析一下每一步的耗时:

- 客户端发出SYNC包:客户端一般是通过connect系统调用来发出 SYN 的,这里牵涉到本机的系统调用和软中断的 CPU 耗时开销

- SYN传到服务器:SYN从客户端网卡被发出,这是一次长途远距离的网络传输

- 服务器处理SYN包:内核通过软中断来收包,然后放到半连接队列中,然后再发出SYN/ACK响应。主要是 CPU 耗时开销

- SYC/ACK传到客户端:长途网络跋涉

- 客户端处理 SYN/ACK:客户端内核收包并处理SYN后,经过几us的CPU处理,接着发出 ACK。同样是软中断处理开销

- ACK传到服务器:长途网络跋涉

- 服务端收到ACK:服务器端内核收到并处理ACK,然后把对应的连接从半连接队列中取出来,然后放到全连接队列中。一次软中断CPU开销

- 服务器端用户进程唤醒:正在被accpet系统调用阻塞的用户进程被唤醒,然后从全连接队列中取出来已经建立好的连接。一次上下文切换的CPU开销

在客户端视角,在正常情况下一次TCP连接总的耗时也就就大约是一次网络RTT的耗时。但在某些情况下,可能会导致连接时的网络传输耗时上涨、CPU处理开销增加、甚至是连接失败。这种时候在发现延时过长之后,就可以结合其他信息进行分析。

ebpf 实现原理

在 TCP 三次握手的时候,Linux 内核会维护两个队列,分别是:

- 半连接队列,也称 SYN 队列;

- 全连接队列,也称 accepet 队列;

服务端收到客户端发起的 SYN 请求后,内核会把该连接存储到半连接队列,并向客户端响应 SYN+ACK,接着客户端会返回 ACK,服务端收到第三次握手的 ACK 后,内核会把连接从半连接队列移除,然后创建新的完全的连接,并将其添加到 accept 队列,等待进程调用 accept 函数时把连接取出来。

我们的 ebpf 代码实现在 https://github.com/yunwei37/Eunomia/blob/master/bpftools/tcpconnlat/tcpconnlat.bpf.c 中:

它主要使用了 trace_tcp_rcv_state_process 和 kprobe/tcp_v4_connect 这样的跟踪点:

SEC("kprobe/tcp_v4_connect")

int BPF_KPROBE(tcp_v4_connect, struct sock *sk)

{

return trace_connect(sk);

}

SEC("kprobe/tcp_v6_connect")

int BPF_KPROBE(tcp_v6_connect, struct sock *sk)

{

return trace_connect(sk);

}

SEC("kprobe/tcp_rcv_state_process")

int BPF_KPROBE(tcp_rcv_state_process, struct sock *sk)

{

return handle_tcp_rcv_state_process(ctx, sk);

}

在 trace_connect 中,我们跟踪新的 tcp 连接,记录到达时间,并且把它加入 map 中:

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, 4096);

__type(key, struct sock *);

__type(value, struct piddata);

} start SEC(".maps");

static int trace_connect(struct sock *sk)

{

u32 tgid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

struct piddata piddata = {};

if (targ_tgid && targ_tgid != tgid)

return 0;

bpf_get_current_comm(&piddata.comm, sizeof(piddata.comm));

piddata.ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

piddata.tgid = tgid;

bpf_map_update_elem(&start, &sk, &piddata, 0);

return 0;

}

在 handle_tcp_rcv_state_process 中,我们跟踪接收到的 tcp 数据包,从 map 从提取出对应的 connect 事件,并且计算延迟:

static int handle_tcp_rcv_state_process(void *ctx, struct sock *sk)

{

struct piddata *piddatap;

struct event event = {};

s64 delta;

u64 ts;

if (BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_state) != TCP_SYN_SENT)

return 0;

piddatap = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&start, &sk);

if (!piddatap)

return 0;

ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

delta = (s64)(ts - piddatap->ts);

if (delta < 0)

goto cleanup;

event.delta_us = delta / 1000U;

if (targ_min_us && event.delta_us < targ_min_us)

goto cleanup;

__builtin_memcpy(&event.comm, piddatap->comm,

sizeof(event.comm));

event.ts_us = ts / 1000;

event.tgid = piddatap->tgid;

event.lport = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_num);

event.dport = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_dport);

event.af = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_family);

if (event.af == AF_INET) {

event.saddr_v4 = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_rcv_saddr);

event.daddr_v4 = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_daddr);

} else {

BPF_CORE_READ_INTO(&event.saddr_v6, sk,

__sk_common.skc_v6_rcv_saddr.in6_u.u6_addr32);

BPF_CORE_READ_INTO(&event.daddr_v6, sk,

__sk_common.skc_v6_daddr.in6_u.u6_addr32);

}

bpf_perf_event_output(ctx, &events, BPF_F_CURRENT_CPU,

&event, sizeof(event));

cleanup:

bpf_map_delete_elem(&start, &sk);

return 0;

}

编译运行

git clone https://github.com/libbpf/libbpf-bootstrap libbpf-bootstrap-cloned- 将 libbpf-bootstrap目录下的文件复制到

libbpf-bootstrap-cloned/examples/c下 - 修改

libbpf-bootstrap-cloned/examples/c/Makefile,在其APPS项后添加tcpconnlat - 在

libbpf-bootstrap-cloned/examples/c下运行make tcpconnlat sudo ./tcpconnlat

效果

root@yutong-VirtualBox:~/libbpf-bootstrap/examples/c# ./tcpconnlat

PID COMM IP SADDR DADDR DPORT LAT(ms)

222564 wget 4 192.168.88.15 110.242.68.3 80 25.29

222684 wget 4 192.168.88.15 167.179.101.42 443 246.76

222726 ssh 4 192.168.88.15 167.179.101.42 22 241.17

222774 ssh 4 192.168.88.15 1.15.149.151 22 25.31

总结

通过上面的实验,我们可以看到,tcpconnlat 工具的实现原理是基于内核的TCP连接的跟踪,并且可以跟踪到 tcp 连接的延迟时间;除了命令行使用方式之外,还可以将其和容器、k8s 等元信息综合起来,通过 prometheus 和 grafana 等工具进行网络性能分析。

来源:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/libbpf-tools/tcpconnlat.bpf.c

eBPF 入门实践教程:编写 eBPF 程序 tcpconnlat 测量 tcp 连接延时

代码解释

背景

在互联网后端日常开发接口的时候中,不管你使用的是C、Java、PHP还是Golang,都避免不了需要调用mysql、redis等组件来获取数据,可能还需要执行一些rpc远程调用,或者再调用一些其它restful api。 在这些调用的底层,基本都是在使用TCP协议进行传输。这是因为在传输层协议中,TCP协议具备可靠的连接,错误重传,拥塞控制等优点,所以目前应用比UDP更广泛一些。但相对而言,tcp 连接也有一些缺点,例如建立连接的延时较长等。因此也会出现像 QUIC ,即 快速UDP网络连接 ( Quick UDP Internet Connections )这样的替代方案。

tcp 连接延时分析对于网络性能分析优化或者故障排查都能起到不少作用。

tcpconnlat 的实现原理

tcpconnlat 这个工具跟踪执行活动TCP连接的内核函数 (例如,通过connect()系统调用),并显示本地测量的连接的延迟(时间),即从发送 SYN 到响应包的时间。

tcp 连接原理

tcp 连接的整个过程如图所示:

在这个连接过程中,我们来简单分析一下每一步的耗时:

- 客户端发出SYNC包:客户端一般是通过connect系统调用来发出 SYN 的,这里牵涉到本机的系统调用和软中断的 CPU 耗时开销

- SYN传到服务器:SYN从客户端网卡被发出,这是一次长途远距离的网络传输

- 服务器处理SYN包:内核通过软中断来收包,然后放到半连接队列中,然后再发出SYN/ACK响应。主要是 CPU 耗时开销

- SYC/ACK传到客户端:长途网络跋涉

- 客户端处理 SYN/ACK:客户端内核收包并处理SYN后,经过几us的CPU处理,接着发出 ACK。同样是软中断处理开销

- ACK传到服务器:长途网络跋涉

- 服务端收到ACK:服务器端内核收到并处理ACK,然后把对应的连接从半连接队列中取出来,然后放到全连接队列中。一次软中断CPU开销

- 服务器端用户进程唤醒:正在被accpet系统调用阻塞的用户进程被唤醒,然后从全连接队列中取出来已经建立好的连接。一次上下文切换的CPU开销

在客户端视角,在正常情况下一次TCP连接总的耗时也就就大约是一次网络RTT的耗时。但在某些情况下,可能会导致连接时的网络传输耗时上涨、CPU处理开销增加、甚至是连接失败。这种时候在发现延时过长之后,就可以结合其他信息进行分析。

ebpf 实现原理

在 TCP 三次握手的时候,Linux 内核会维护两个队列,分别是:

- 半连接队列,也称 SYN 队列;

- 全连接队列,也称 accepet 队列;

服务端收到客户端发起的 SYN 请求后,内核会把该连接存储到半连接队列,并向客户端响应 SYN+ACK,接着客户端会返回 ACK,服务端收到第三次握手的 ACK 后,内核会把连接从半连接队列移除,然后创建新的完全的连接,并将其添加到 accept 队列,等待进程调用 accept 函数时把连接取出来。

我们的 ebpf 代码实现在 https://github.com/yunwei37/Eunomia/blob/master/bpftools/tcpconnlat/tcpconnlat.bpf.c 中:

它主要使用了 trace_tcp_rcv_state_process 和 kprobe/tcp_v4_connect 这样的跟踪点:

SEC("kprobe/tcp_v4_connect")

int BPF_KPROBE(tcp_v4_connect, struct sock *sk)

{

return trace_connect(sk);

}

SEC("kprobe/tcp_v6_connect")

int BPF_KPROBE(tcp_v6_connect, struct sock *sk)

{

return trace_connect(sk);

}

SEC("kprobe/tcp_rcv_state_process")

int BPF_KPROBE(tcp_rcv_state_process, struct sock *sk)

{

return handle_tcp_rcv_state_process(ctx, sk);

}

在 trace_connect 中,我们跟踪新的 tcp 连接,记录到达时间,并且把它加入 map 中:

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, 4096);

__type(key, struct sock *);

__type(value, struct piddata);

} start SEC(".maps");

static int trace_connect(struct sock *sk)

{

u32 tgid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

struct piddata piddata = {};

if (targ_tgid && targ_tgid != tgid)

return 0;

bpf_get_current_comm(&piddata.comm, sizeof(piddata.comm));

piddata.ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

piddata.tgid = tgid;

bpf_map_update_elem(&start, &sk, &piddata, 0);

return 0;

}

在 handle_tcp_rcv_state_process 中,我们跟踪接收到的 tcp 数据包,从 map 从提取出对应的 connect 事件,并且计算延迟:

static int handle_tcp_rcv_state_process(void *ctx, struct sock *sk)

{

struct piddata *piddatap;

struct event event = {};

s64 delta;

u64 ts;

if (BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_state) != TCP_SYN_SENT)

return 0;

piddatap = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&start, &sk);

if (!piddatap)

return 0;

ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

delta = (s64)(ts - piddatap->ts);

if (delta < 0)

goto cleanup;

event.delta_us = delta / 1000U;

if (targ_min_us && event.delta_us < targ_min_us)

goto cleanup;

__builtin_memcpy(&event.comm, piddatap->comm,

sizeof(event.comm));

event.ts_us = ts / 1000;

event.tgid = piddatap->tgid;

event.lport = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_num);

event.dport = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_dport);

event.af = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_family);

if (event.af == AF_INET) {

event.saddr_v4 = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_rcv_saddr);

event.daddr_v4 = BPF_CORE_READ(sk, __sk_common.skc_daddr);

} else {

BPF_CORE_READ_INTO(&event.saddr_v6, sk,

__sk_common.skc_v6_rcv_saddr.in6_u.u6_addr32);

BPF_CORE_READ_INTO(&event.daddr_v6, sk,

__sk_common.skc_v6_daddr.in6_u.u6_addr32);

}

bpf_perf_event_output(ctx, &events, BPF_F_CURRENT_CPU,

&event, sizeof(event));

cleanup:

bpf_map_delete_elem(&start, &sk);

return 0;

}

编译运行

TODO

总结

通过上面的实验,我们可以看到,tcpconnlat 工具的实现原理是基于内核的TCP连接的跟踪,并且可以跟踪到 tcp 连接的延迟时间;除了命令行使用方式之外,还可以将其和容器、k8s 等元信息综合起来,通过 prometheus 和 grafana 等工具进行网络性能分析。

Eunomia是一个使用 C/C++ 开发的基于 eBPF的轻量级,高性能云原生监控工具,旨在帮助用户了解容器的各项行为、监控可疑的容器安全事件,力求提供覆盖容器全生命周期的轻量级开源监控解决方案。它使用LinuxeBPF技术在运行时跟踪您的系统和应用程序,并分析收集的事件以检测可疑的行为模式。目前,它包含性能分析、容器集群网络可视化分析*、容器安全感知告警、一键部署、持久化存储监控等功能,提供了多样化的 ebpf 追踪点。其核心导出器/命令行工具最小仅需要约 4MB 大小的二进制程序,即可在支持的 Linux 内核上启动。

项目地址:https://github.com/yunwei37/Eunomia

参考资料

eBPF入门实践教程:使用 libbpf-bootstrap 开发程序统计 TCP 连接延时

tcpstates 是一个追踪当前系统上的TCP套接字的TCP状态的程序,主要通过跟踪内核跟踪点 inet_sock_set_state 来实现。统计数据通过 perf_event向用户态传输。

SEC("tracepoint/sock/inet_sock_set_state")

int handle_set_state(struct trace_event_raw_inet_sock_set_state *ctx)

在套接字改变状态处附加一个eBPF跟踪函数。

if (ctx->protocol != IPPROTO_TCP)

return 0;

if (target_family && target_family != family)

return 0;

if (filter_by_sport && !bpf_map_lookup_elem(&sports, &sport))

return 0;

if (filter_by_dport && !bpf_map_lookup_elem(&dports, &dport))

return 0;

跟踪函数被调用后,先判断当前改变状态的套接字是否满足我们需要的过滤条件,如果不满足则不进行记录。

tsp = bpf_map_lookup_elem(×tamps, &sk);

ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

if (!tsp)

delta_us = 0;

else

delta_us = (ts - *tsp) / 1000;

event.skaddr = (__u64)sk;

event.ts_us = ts / 1000;

event.delta_us = delta_us;

event.pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

event.oldstate = ctx->oldstate;

event.newstate = ctx->newstate;

event.family = family;

event.sport = sport;

event.dport = dport;

bpf_get_current_comm(&event.task, sizeof(event.task));

if (family == AF_INET) {

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&event.saddr, sizeof(event.saddr), &sk->__sk_common.skc_rcv_saddr);

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&event.daddr, sizeof(event.daddr), &sk->__sk_common.skc_daddr);

} else { /* family == AF_INET6 */

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&event.saddr, sizeof(event.saddr), &sk->__sk_common.skc_v6_rcv_saddr.in6_u.u6_addr32);

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&event.daddr, sizeof(event.daddr), &sk->__sk_common.skc_v6_daddr.in6_u.u6_addr32);

}

使用状态改变相关填充event结构体。

- 此处使用了

libbpf的 CO-RE 支持。

bpf_perf_event_output(ctx, &events, BPF_F_CURRENT_CPU, &event, sizeof(event));

将事件结构体发送至用户态程序。

if (ctx->newstate == TCP_CLOSE)

bpf_map_delete_elem(×tamps, &sk);

else

bpf_map_update_elem(×tamps, &sk, &ts, BPF_ANY);

根据这个TCP链接的新状态,决定是更新下时间戳记录还是不再记录它的时间戳。

用户态程序

while (!exiting) {

err = perf_buffer__poll(pb, PERF_POLL_TIMEOUT_MS);

if (err < 0 && err != -EINTR) {

warn("error polling perf buffer: %s\n", strerror(-err));

goto cleanup;

}

/* reset err to return 0 if exiting */

err = 0;

}

不停轮询内核程序所发过来的 perf event。

static void handle_event(void* ctx, int cpu, void* data, __u32 data_sz) {

char ts[32], saddr[26], daddr[26];

struct event* e = data;

struct tm* tm;

int family;

time_t t;

if (emit_timestamp) {

time(&t);

tm = localtime(&t);

strftime(ts, sizeof(ts), "%H:%M:%S", tm);

printf("%8s ", ts);

}

inet_ntop(e->family, &e->saddr, saddr, sizeof(saddr));

inet_ntop(e->family, &e->daddr, daddr, sizeof(daddr));

if (wide_output) {

family = e->family == AF_INET ? 4 : 6;

printf(

"%-16llx %-7d %-16s %-2d %-26s %-5d %-26s %-5d %-11s -> %-11s "

"%.3f\n",

e->skaddr, e->pid, e->task, family, saddr, e->sport, daddr,

e->dport, tcp_states[e->oldstate], tcp_states[e->newstate],

(double)e->delta_us / 1000);

} else {

printf(

"%-16llx %-7d %-10.10s %-15s %-5d %-15s %-5d %-11s -> %-11s %.3f\n",

e->skaddr, e->pid, e->task, saddr, e->sport, daddr, e->dport,

tcp_states[e->oldstate], tcp_states[e->newstate],

(double)e->delta_us / 1000);

}

}

static void handle_lost_events(void* ctx, int cpu, __u64 lost_cnt) {

warn("lost %llu events on CPU #%d\n", lost_cnt, cpu);

}

收到事件后所调用对应的处理函数并进行输出打印。

编译运行

git clone https://github.com/libbpf/libbpf-bootstrap libbpf-bootstrap-cloned- 将 libbpf-bootstrap目录下的文件复制到

libbpf-bootstrap-cloned/examples/c下 - 修改

libbpf-bootstrap-cloned/examples/c/Makefile,在其APPS项后添加tcpstates - 在

libbpf-bootstrap-cloned/examples/c下运行make tcpstates sudo ./tcpstates

效果

root@yutong-VirtualBox:~/libbpf-bootstrap/examples/c# ./tcpstates

SKADDR PID COMM LADDR LPORT RADDR RPORT OLDSTATE -> NEWSTATE MS

ffff9bf61bb62bc0 164978 node 192.168.88.15 0 52.178.17.2 443 CLOSE -> SYN_SENT 0.000

ffff9bf61bb62bc0 0 swapper/0 192.168.88.15 41596 52.178.17.2 443 SYN_SENT -> ESTABLISHED 225.794

ffff9bf61bb62bc0 0 swapper/0 192.168.88.15 41596 52.178.17.2 443 ESTABLISHED -> CLOSE_WAIT 901.454

ffff9bf61bb62bc0 164978 node 192.168.88.15 41596 52.178.17.2 443 CLOSE_WAIT -> LAST_ACK 0.793

ffff9bf61bb62bc0 164978 node 192.168.88.15 41596 52.178.17.2 443 LAST_ACK -> LAST_ACK 0.086

ffff9bf61bb62bc0 228759 kworker/u6 192.168.88.15 41596 52.178.17.2 443 LAST_ACK -> CLOSE 0.193

ffff9bf6d8ee88c0 229832 redis-serv 0.0.0.0 6379 0.0.0.0 0 CLOSE -> LISTEN 0.000

ffff9bf6d8ee88c0 229832 redis-serv 0.0.0.0 6379 0.0.0.0 0 LISTEN -> CLOSE 1.763

ffff9bf7109d6900 88750 node 127.0.0.1 39755 127.0.0.1 50966 ESTABLISHED -> FIN_WAIT1 0.000

对于输出的详细解释,详见 README.md

总结

这里的代码修改自 https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/libbpf-tools/tcpstates.bpf.c

eBPF 入门实践教程:编写 eBPF 程序 Tcprtt 测量 TCP 连接的往返时间

背景

网络质量在互联网社会中是一个很重要的因素。导致网络质量差的因素有很多,可能是硬件因素导致,也可能是程序